Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

De Urbanisten: From drain to sponge city

We need to ‘depave’ our cities street by street, says De Urbanisten’s Dirk van Peijpe, whose famous water squares combine climate resilience with public space. Christine Murray reports

“How do we deal with this climate crisis and can we do it in such a way that we also create spaces that add value to the community and their quality of life?” asks Dirk van Peijpe, founder of Rotterdam urban design studio, De Urbanisten.

We’re talking about De Urbanisten’s Water Square project in Rotterdam, which famously doubles up flood-proofing with public space. But van Peijpe could be summing up the challenge facing city leaders across the UK.

Fresh evidence shows sea levels are rising at an unprecedented rate, and the latest report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that by 2050, those one-in-100-year weather events could happen every year, unless the global population dramatically curbs emissions.

It is a scary statistic when you realise that 10% of all new homes built in England since 2013 were constructed in high-risk flood zones, according to recent analysis of government by The Guardian. Built with a “one in 100 or greater annual probability of river flooding”, a staggering 53% of all new homes built in Newham and 48% of those in North Somerset in 2016-17. And the rate at which the UK is building homes on the floodplain is accelerating.

As a result, there has been a rise in planning rejections for schemes that do not include flood-proofing by design.

These are set to increase further with new requirements that force developments to reduce run-off from cloudbursts with features such as swales.

In Hull, where 98% of all homes are at high risk of flooding, the inclusion of sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) in all new developments is now legally binding. Wales has also made SuDS inclusion mandatory.

Other local authorities are prioritising sustainable drainage in line with the National Planning Policy Framework, which stipulates that SuDS should be given first preference in development plans. New guidelines coming into effect in April 2020 with Sewage for Adoption 8 will also see planning authorities updating their policies to align with new Ofwat standards.

Now, with flooding hitting the headlines after a seasonal drought in London, plus the recent climate strikes and the growing public clamour for greener cities with less toxic air, it is understandable that water excess and shortage, air quality and biodiversity have rocketed up the planning agenda.

Rotterdam, on the other hand, has been facing the threat of floods for hundreds of years, so the city is ahead of the UK when it comes to innovation in urban water solutions. As such, its designers are also sought after as leaders in water-sensitive design – one of the reasons van Peijpe, by popular demand, was been invited to present his work at The Developer Live: Risk & Resilience conference. His talk is now available on podcast.

Although it has been five years since De Urbanisten celebrated the opening of Benthemplein, its first water square, delegations still enthusiastically visit this once-empty public space every year.

When it rains, the basketball and skateboarding courts become water collection ponds. The water is retained for a day or two until it drains into the ground or is pumped into a nearby canal

When dry, which is 90% of the time, its three basins serve as basketball and skateboarding courts. During a cloudburst or flash flood, the water is filtered before it enters the square and runs out of spouts and along gutters until it fills the play courts, which become water collection ponds. The water is retained for a day or two until it drains into the ground or is pumped into a nearby canal.

“The critical point is that none of the water goes into the sewers,” says van Peijpe.

The concept was borne out of what van Peijpe calls “our first wake-up call to climate change”, in 2006, following the publication of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth.

Rotterdam had been investing in expensive underground rainwater tanks to prevent the overwhelming of the sewage system. De Urbanisten’s idea was to take these technical drainage projects and combine them with a public space need in dense neighbourhoods.

One benefit to this was the opportunity to combine the city’s wastewater budget with a public space grant.

“When you can link it to other programmes and needs, you can stack your budget,” says van Peijpe. “Sixty per cent of the finance was paid out of funding dedicated to sewage renewal, with 40% of the budget linked to city beautification.”

This holistic approach is the hallmark of ‘resilience’, a concept encouraged by movements such as the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities project, founded on the idea that city budgets for maintenance and upgrades could be combined with the need for environmental improvements.

“We now want to move away from drainage completely, to keep the water in the square, either in the soil or some kind of aquifer”

The 100 Resilient Cities programme is being wound down, but its fundamental ethos of breaking down silos and combining budgets has transformed the way some cities spend their money, including Rotterdam. Instead of a pot for road maintenance, there might be a pot for more liveable streets, and the money is spent on anything that contributes to a top-line vision of what they would like to achieve.

Van Peijpe says resilient thinking has even led to schools upgrading city drainage systems as part of playground projects: “They can provide children with greener playgrounds while installing rainwater collection.”

I ask van Peijpe what he has learned in the five years since the opening of his water square, and he reveals that his thinking has shifted dramatically.

He says: “Fundamentally, we took a drainage approach – we drained the water, even if it didn’t go into the sewer. We now want to move away from drainage completely, to keep the water in the square, either in the soil or some kind of aquifer.

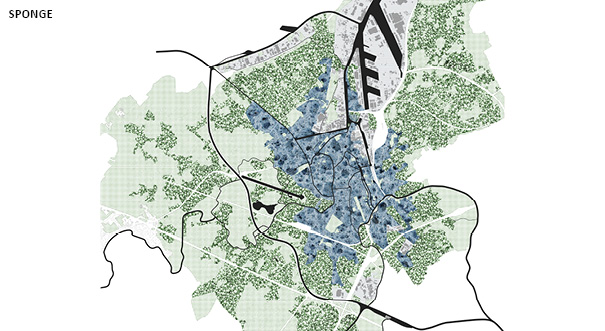

“We need to move from being a drainage city to a sponge city.”

He adds that China is working on a massive programme along these lines.

“We want to keep the water in the city and be able to bring it back when we need it. Climate adaptation and resilience is about dealing with extremes – too much water or too little. Through soil with sponge conditions, such as peat, clay or rubble, and certain plantings, or even by replenishing aquifers, we can absorb excess water but get it back during droughts.”

“Climate adaptation and resilience is about dealing with extremes – too much water, or too little. [In a sponge city] we can absorb excess water but get it back during droughts”

Pilot sites are viewed as critical to testing De Urbanisten’s ideas and near its office, it is now experimenting with a sponge garden. The firm recently tweeted how impressed it has been with the garden’s resistance to drought.

Another shift for van Peijpe is the move to ‘depave’ our cities. Both an activist movement and design approach, depaving involves literally digging up the pavement or asphalt to create more permeable, greener streets.

He says: “The reality is that most public spaces are designed not by landscape architects or other architects, but by traffic engineers.”

Depaving takes a street-by-street approach. Van Peijpe explains: “You look at how much paving you actually need, for vehicles, parking and so-on. Then you remove as much as possible to incorporate plantings, rainwater or infiltration tanks.”

This should make the streets more resilient, and more attractive, he argues, and depaving can be incorporated into road improvement plans.

“Instead of just maintaining roads, with the same money you can make the city more resilient,” he says.

But van Peijpe admits that changing the mindset of traffic engineers and road maintenance crews is necessary. Test projects can help with this – but he says they are also considering publishing guidance.

“Appreciation is growing for a different sort of green... It’s low-maintenance, lush and the community is looking after it”

Overall, he is optimistic about its widespread adoption. “Depaving is already going on in the first metre outside people’s houses, where they are planting it themselves.”

On a recent trip to Paris, van Peijpe was also impressed by community gardens sprouting around the base of city trees. He says: “These explosions of wildflowers are a radical departure from formal French gardening. It shows me that an appreciation is growing for a different sort of green. These ecosystems provide more than functional drainage value as well, such as flora and fauna, contributing to active healthy living and they raise the value of the real estate, too.

“Cities are more and more considered attractive places where people want to stay. People who really want to stay also want to take care of their front yard. We have a more active population, and people are involved in making their own environment greener and softer. It’s low-maintenance, lush and green, and the community is looking after it.”

Support The Developer on Patreon

Our journalism has always been free-to-air.

If you value what we publish, be our patron from £3 per month

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238