Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Wellbeing is rarely one size fits all: Its definition shifts depending on how people live

To put the Wellbeing Economy into practice, we need to have deeper conversations to uncover the complex, knotty, place-specific challenges that designing for wellbeing poses, Milly Warner reports

Social Impact Researcher

Stride Treglown

"What does wellbeing mean to you?” It’s a deceptively simple question. But for the small village of Glyn-coch, nestled in the valleys of South Wales, it was the starting point for our action research project.

The process was part of a wider project to create an “educational, community and well-being hub” for the town by merging two existing schools into a single new centre.

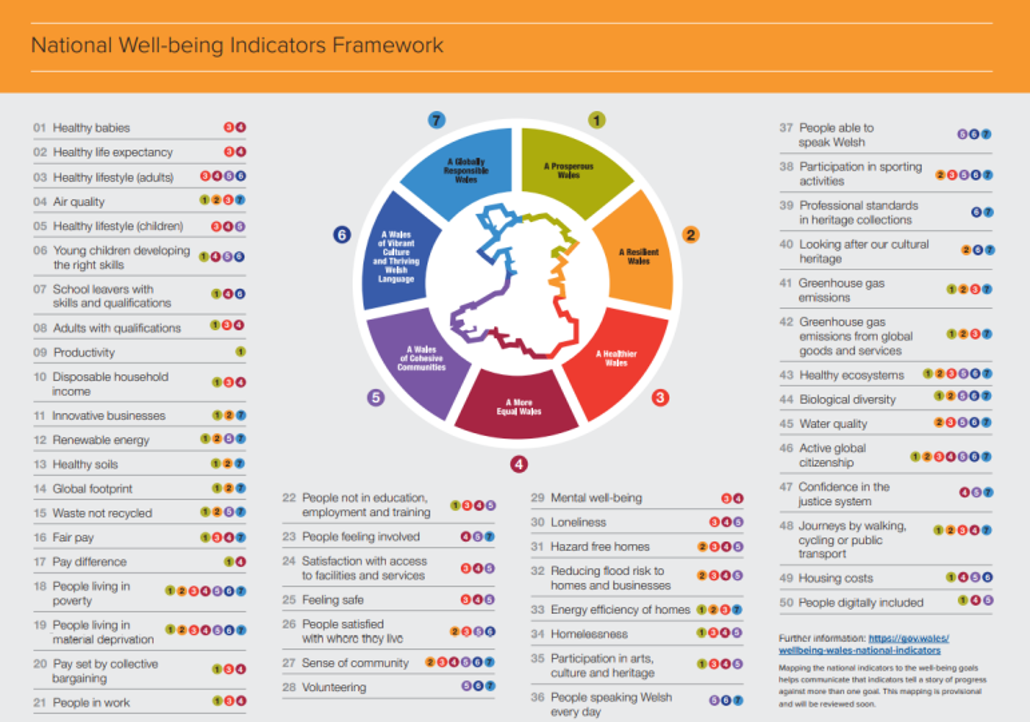

This was part of the Welsh Government’s Sustainable Schools’ Challenge, which supported three pathfinder projects across Wales and explored different models for developing capital infrastructure projects under the framing of the Well-being of Future Generations Act. The act was passed in 2015 and aims to ensure that public bodies take decisions that ensure future generations have at least the same quality of life as we do now.

To meet this challenge we knew we’d need a deeper, more relational approach to community engagement

The brief made the challenge clear: wellbeing is rarely one size fits all. Its definition shifts depending on who lives within a community and what their lives look like. It raised the difficult question — could the project deliver on each of the brief’s complex ambitions simultaneously?

Typically, this question would be answered during a series of quick-fire engagement sessions in a town hall, accompanied by a selection of designs for people to feedback on.

But to meet this challenge, we knew we’d need a deeper, more relational approach to help us understand the complex, knotty challenges that designing for wellbeing poses.

Over four months, we joined tea and cake mornings, community lunches, and teacher-parent days to hear stories of life in Glyn-coch. We spoke with parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, teachers, ex-pupils, school Governors and community leaders.

Joining these events helped us to meet with people across the community. In time, this led to seventeen in-depth, semi-structured interviews.

Tucked away in a little classroom surrounded by student art or set up in the far corner of the Community Centre fuelled by an endless supply of tea, we discussed participants’ experiences of wellbeing in relation to the indicators outlined in the Well-being of Future Generations Act.

The stories we heard were revealing. They showed that, whilst some of the ways the act defined wellbeing resonated with local people, others didn’t feature in their lives at all. By listening to local people more deeply, we were able to understand how wellbeing is place-based, person-specific, and interconnected in a host of complex ways within Glyn-coch.

One Governor explained the connections between vandalism in the area and a lack of service provision, drawing a link between social and infrastructural challenges: “Kids do destroy the building, you know, they’ll smash this, and climb on the roofs […] they could do with more areas to play, to kick a ball.”

Likewise, a teacher described difficulty engaging with health services due to a range of transport and educational barriers, reflecting that “it’s almost like the services need to come to you, isn’t it?”

Dozens of insights like these fed into a locally specific framing of well-being unique to Glyn-coch — one that acknowledged the interconnectedness of social, economic and infrastructural conditions

Another teacher explained how early interactions with families were essential to enhance collective wellbeing; “You should be engaging with that parent when she’s pregnant […] I think just in general building those relationships and having a team around the children and us promotes the health and promotes the wellbeing of all.”

Meanwhile, parents linked well-being to experiences such as a sense of ownership and pride. They explained, “I think giving [the children] that bit of ownership they take pride in it more [...] That gives them a sense of wellbeing then as well because they feel part of the school and the community as a family rather than then just coming here and being told what to do”.

Dozens of insights like these fed into a locally specific framing of wellbeing unique to Glyn-coch — one that acknowledged the interconnectedness of social, economic and infrastructural conditions.

We then coded the transcripts, translating stories into actionable data for the wider project team. This was done in two key stages.

First, we coded the transcripts based on the indicator themes the research had been designed to explore, such as people’s feelings of safety, community, and satisfaction with their area. Second, we coded them based on other important ideas that came up in conversation, like pride, heritage, and a sense of care.

Now came the hard part— how do you turn deep listening into tangible action?

Once those two stages were complete, we undertook a co-occurrence analysis, which helped us to understand the connections between the different social and infrastructural dynamics the interviews had identified. The result was a deeper understanding of what was meaningful to the local community.

Across all our conversations, three common layers of wellbeing emerged: service provision, safety and security, and community relationships. Now came the hard part— how do you turn deep listening into tangible action?

In the case of Glyn-coch, the new school’s design actively responded to the layers of wellbeing that our interviews identified. It focused on enhancing service provision by collocating dedicated community support facilities. Some of the perceived causes of security challenges were tackled by creating accessible playing fields to give teenagers space to play and alleviate boredom. Opportunities for enhanced community relationships were provided by new intergenerational growing spaces, which enabled previously isolated neighbours to meet and connect.

So, what did we learn from the process? At a macro scale, the Wellbeing Economy— the theoretical concept that guides the Well-being of Future Generations Act— intends to respond to intersecting and mutually reinforcing crises affecting our social, economic, and environmental systems.

Our Glyn-coch example shows how, at a local level, this theoretical framing can be grounded in practice. Our interviews illustrate that, to local communities, wellbeing is fundamentally rooted in place, moving from a national framing to a unique local context.

Ultimately, both under-performing and well-performing infrastructure has clear well-being implications at both the micro and macro level. The associated costs and benefits are immediately borne by the community and, in time, by the state through the reparative work of bodies such as the Department for Health and Social Care and Department for Education.

As the well-known mantra goes, prevention is better than cure. Explicitly asking local people what well-being means to them is an opportunity to be both innovative and practical. It helps to develop a roadmap for locally-rooted, evidence-based implementation at the project level, whilst delivering social and infrastructural benefits to strive towards Wellbeing Economy in practice.

Milly Warner, Social Impact Researcher, Stride Treglown, is an urban researcher, planner and designer whose work explores socially just, economically inclusive, and environmentally sustainable approaches to urban development.

Find out more Read the Glyn-coch Primary School Impact Analysis Report

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238