Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

How the new NPPF puts design back at the heart of planning

What you need to know about the draft NPPF and Planning Practice Guidance before the government consultation ends on 10 March by Hilary Satchwell

After years of erosion, the role of design is back in the planning system and focused on what really matters: High-quality places for the people who live in them.

The new draft of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) feels like it’s come from a government that is listening. It recognises that the challenge is not simply about how many homes are delivered, but how the planning system can support the delivery of homes and places that will work in practice.

In doing so, it begins to realign planning and design in a way that is long overdue.

I’ve spent nearly 30 years working in and around design policy and guidance in the English planning system, and this feels quite exciting. Professor Matthew Carmona agrees, with the longtime analyst of design quality in England writing that the December 2025 draft NPPF “marks genuine progress towards clarity.”

But what do these changes actually mean for the way we work, and how should we respond to the government consultation?

The draft NPPF begins to realign planning and design in a way that is long overdue

We need this change. Much of the last decade has been contradictory for design and placemaking in the planning system. We’ve added layers of complexity across a broad range of largely non-design topics whilst simultaneously watering down the importance of design at national level, and then been told it’s all about beauty.

We’ve also had mixed signals from government about planning for growth while preserving everything as it is. Last year’s mini update to the NPPF sorted out some of these clashes – for example, reconfirming the role of a wider range of design tools and not just design codes. But the confusion left many Planning Authorities unwilling or unable to refuse applications on design grounds, fearful of losing appeals in a system that has undermined their ability to do so given housing delivery targets.

In contrast, the new NPPF acknowledges that, if well-designed and considered, change can be good.

The NPPF takes a reasonably people-centred approach on areas where change is needed most: density, climate change, sustainability and a clear preference for transit-oriented development

We know that places and buildings that are well designed affect people’s lives positively, from the way they live in their homes to whether they feel part of their neighbourhood; from the transport choices they have to their access to job opportunities and cultural experiences. Daily joy and connection can also help build resilience.

It is also especially hard to get anything built at the moment – no-one in the industry is going to be asking for policy with gold taps. But we do need to keep pushing for well-designed, climate resilient and people-friendly places that actually work for the communities who use them now and for the long term.

What we want is consistent national messaging that design and placemaking is a vital consideration within the planning system; an agreed definition as to what this means and a clear link between policy and how planning decisions are made. Is this what we have got in the draft NPPF?

Well, good placemaking is much more front and centre. The places section has been rewritten and is much clearer on what is expected. It also relates to a wider range of other topics that impact on quality placemaking – with human connection, nature and accessibility in mind.

Perhaps the most important update for design is that the NPPF even more explicitly states that proposals that are not well designed should be refused planning permission

The emphasis is on the fundamentals of what homes and neighbourhoods need to function. Much of the focus is on placemaking (very simply ‘the making of places’), and much less about individual buildings, which is entirely to be expected from a National Policy document. It takes a reasonably people-centred approach on areas where change is needed most: density, climate change, sustainability and a clear preference for transit-oriented development – a movement that has been growing for a while.

The principles of place-design emphasise the importance of responding to context with clear intent around innovation and change. Importantly, the NPPF places greater responsibility on local authorities to plan not just for housing numbers, but to articulate the kind of places that should be delivered to reflect the characteristics and needs of each area. This has the potential to be quite a step change, requiring clear thinking on place and quality at all levels.

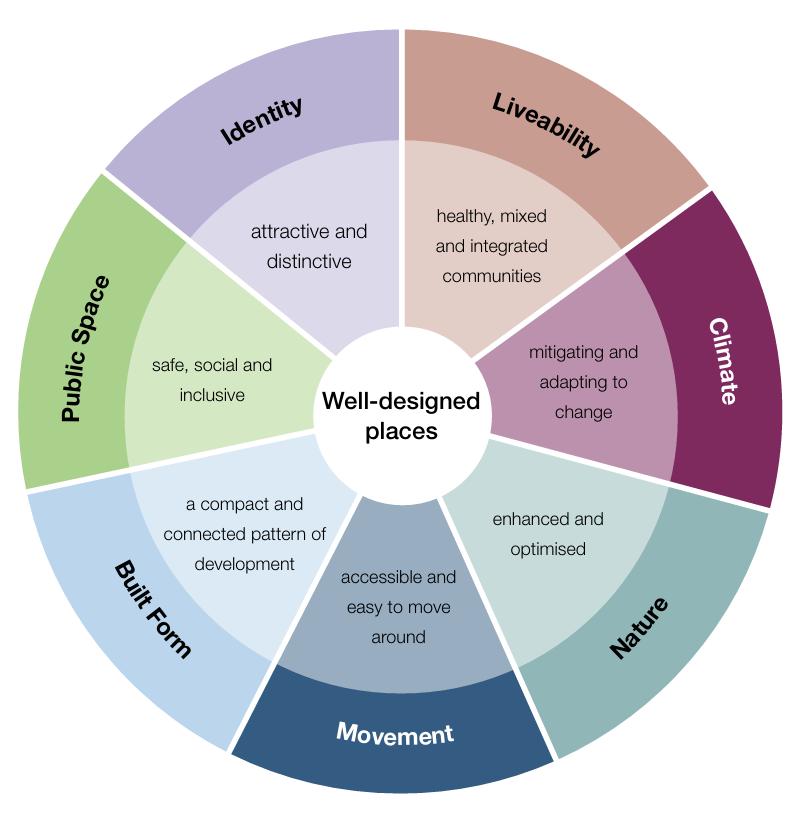

Perhaps the most important update is that the NPPF explicitly states that proposals that are not well-designed should be refused planning permission. The policy also defines what “well-designed” actually means through eight key principles – an evolution of the previous ten principles in the National Design Guide: Context, liveability, climate, nature, movement, built form, public space and identity. Seven of these principles are repeated in the accompanying Design and Placemaking Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) as ‘features of well-designed places’ – where context is given a different treatment.

Crucially, these changes don’t rely on complex or costly new mechanisms at a time when both public and private sectors are under pressure. The eight principles are about clarity, alignment and using the range of design tools and processes we already have more effectively, but with purpose and vision.

There is a strong requirement for local authorities to use planning policy set out design expectations that look ahead to what they want to achieve, and to define the tools they believe are necessary to get there. If it works, the draft NPPF really is “front-loading” place, making sure that what we mean by change is properly thought about earlier on in the process.

Structurally, the document is much clearer. Sections that influence how planning decisions are made (national decision-making policies) are clearly identified and separate from those covering plan-making.

It’s important to read the NPPF holistically and to look beyond the excellent well-designed places section. There are clear design implications and inter-relationships across nearly all other sections of the document. An example of this relates to how the document deals with flood risk and coastal change – this now has its own section that expects this issue to be considered from the very beginning of both the site allocation and design process, and removes some of the ambiguity from previous versions.

The accompanying Design and Placemaking Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) is a well-structured useful tool that provides an updated version of the National Design Guide, the design sections of the online planning practice guidance, and an update to the National Model Design Code, all in a single 150-page document. Its purpose is to define well-designed places and the processes and tools needed to deliver it.

Part one breaks down the seven features of well-designed places. Intended for a broad audience – from local authorities to councillors, design teams and communities – it is practical and easy-to-read. The guide describes what is important in thinking about place and buildings and, for the first time, gives us "shoulds" and "musts", such as “buildings and places should be fit for purpose, durable and bring delight.” What’s not to agree with there?

Part two is about design quality in the planning system and is more focussed on the processes and tools that we can use to help make good places. It is necessarily light touch in some areas and sets out a simple structure for making a masterplan and preparing a design code, as well as providing guidance for local authorities in how they should include design in their plan-making process which is important given the NPPFs focus on properly vision led local plans that go beyond a few nice words to actually describing the change that they want to see come about.

The third part is about how to prepare good design codes and is focussed on local area codes more than site-based codes. It follows on from the Pathfinder work undertaken by MHCLG in the last few years and the publication of the National Model Design code. It sets out what can be coded for and where, with an emphasis on adding clarity and value. These principles could also be useful for design teams producing site-based codes for larger and strategic sites.

What’s missing? Health inequalities and violence against women and girls

There is much to celebrate, but there are also gaps and contradictions that could be resolved through the consultation process. We need to be realistic about how far national policy and guidance will go to address specific issues, but the consultation is a good opportunity to suggest ways to refine and sharpen both the NPPF and PPG.

The draft NPPF doesn’t adequately highlight the specific needs of key groups in a way that we know makes better places for all. Children and play have been added to this version much more explicitly, which is welcome, but the safety of women and girls is not covered in the NPPF – although there are some possible hooks to include this in the section about planning for clean and safe places.

The safety of women and girls is mentioned, however, in the PPG, where it describes the planning of transport and travel routes, public spaces, security and addressing the fear of crime. Campaigners are calling for the prevention of violence against women and girls to be added to the NPPF, most recently in a letter signed by Liberal Democrat MPs Anna Sabine and Gideon Amos.

Organisations such as the TCPA are very concerned about the weakening of health impacts and inequalities when compared to the existing NPPF. While health is mentioned in the draft document, there is no specific purpose stating that planning must promote health and reduce health inequalities – this is a downgrade from the 2024 NPPF. The TCPA writes: “Current law and governance reforms are aiming to tackle health inequalities as a core purpose, but this revised NPPF removes that very same purpose from national planning guidance, making the timing of this change by MHCLG baffling.”

There is worry about whether the provisions on where to build are strong enough to ensure well-located and accessible development. Whether this will lead to development everywhere and anywhere all at once isn’t yet clear, but that is the risk.

The density minimums are trying to nudge us towards more sustainable and less baggy development forms

Whilst the focus on medium density compact development has been broadly welcomed, there is some concern that the specifics of what is needed to make this work is a bit light on detail and left for local authorities to solve. Esther Kurland from UDL has pointed out that the fundamental relationship between density, travel and access to services at different distances needs better consideration so we can be clearer on what to plan for in new neighbourhoods.

The density minimums proposed in the draft NPPF (40 dwellings per hectare within reasonable walking distance of a railway station, and 50 dwellings per hectare where the station or stop is “well connected”) may seem unambitious to those working in urban locations while unattainable to others in rural areas, even those reasonably well-connected. In reality, these levels are simply trying to nudge us towards more sustainable and less baggy development forms that struggle to support the shops and services that people really need, ideally within walking distance of where they live.

This topic is covered much more comprehensively in the PPG where it makes clear that “higher density development depends on easy access to a range of local facilities and good public transport provision to important destinations.” It references optimising density based on good design rather than simply applying metrics. But the PPG doesn’t specifically guide us on how to deal with the barriers to the delivery of medium density development, such as excessive overlooking distances and high car-parking standards in otherwise accessible locations.

There is some criticism in the industry that the eight key principles in the NPPF and overlapping seven features of well-designed places in the PPG mix up too many ideas and aren’t clearly one thing or another. But I think we need to ask a different question: As set out, are they useful in putting together proposals, reviewing schemes and making the case for good design and place? For me, the answer is a clear yes.

On the one hand, local authorities are required to take a proactive approach to mitigating climate change while on the other, they are not allowed to ask for more than minimum standards. This seems a contradiction

Lastly, the issue that many are grappling with is to do with limitations on the ability of local authorities to set their own standards. The NPPF limits quantitative standards specifically (apart from related to infrastructure provision, affordable housing, car parking, design and placemaking) and confirms that they must not cover matters addressed in the Building Regulations, other than accessibility or water efficiency.

My reading of this is that standards related to design are not excluded and are intended to be included where needed by local authorities. But there is some conflict here: On the one hand, it could be read that local authorities are required to take a proactive approach to mitigating climate change and transition to net zero. On the other hand, they are not allowed to ask for more than the minimum standards already in place. This seems a contradiction.

There is no reason to put off using the draft NPPF’s eight principles of well-designed places in your work now. It’s likely that we won’t have final versions of these documents until the summer, but you don’t have to wait. Talk about the seven features of well-designed places with clients and in pre-apps with planning officers and statutory consultees, use them to structure your design and access statements, and make them the basis of conversations with communities about what well-designed places mean to them. Down the line you will need evidence, such as from a design review panel, to how to show these principles have been met.

For those of us involved in putting together design and placemaking proposals and working with the planning system, our job is to make the case positively for good design and deliverable places that benefit the communities they serve. The draft NPPF reconfirms the broad range of tools that help to create good design, from design review to design codes and design guidance, and masterplans. It even gives substantial weight to outstanding and innovative designs that raise local standards.

The PPG includes practical information about the design process for larger sites, such as when to use design coding and guidance and a range of engagement tools and techniques. It also confirms the importance of spatial design at the larger scale, in making sure we have places that work in terms of urban form and strategic connections. None of this is entirely new – it’s an evolution and refocussing of what we have already. It should not be so different as to change the direction of most well-designed projects or plans.

The industry should respond to the NPPF consultation and include what works well and what needs clarifying

It is very important that those involved in design and placemaking respond to the consultation and provide feedback. Include what you think works well and what lacks clarity, conflict or a risk of unintended consequences. As an example, I can see one or two places where the push towards medium-density compact development is inadvertently undermined by words that imply there should be no change.

The consultation on the draft National Planning Policy Framework and the consultation on the Planning Practice Guidance are open now with specific questions to address and a submission deadline of 10 March 2026. Each has questions to be submitted via an online survey or by email. Make your voice heard.

There will, of course, be pushback on aspects of this new framework, challenges through the planning courts, and it will take time for planning officers and those involved in design to fully embed what it means. But it’s unlikely that this is going away. Why wait when the helpful principles for well-designed places can be useful to us now.

Hilary Satchwell is the director of Tibbalds, Mayor’s Design Advocate for the Mayor of London, co-chair Design South East and a founding member and director of Part W.

8 Key principles for well-designed places

Context: Respond to the history, character and features of the site and its setting, so that it integrates into and enhances its surroundings (such as through the arrangement of development plots and buildings, the use of materials and architectural features, and the restoration, reuse and integration of heritage assets). This should not preclude innovation and change where appropriate, especially where an increased scale or density of development is justified in accordance with policies

Liveability: Support healthy, mixed, vibrant and integrated communities, which will function well over the lifetime of the development, by incorporating a range of uses and tenures, employing features which promote social interaction, and which are robust, durable and easy to look after

Climate: Contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation and the transition to net zero, by using building layouts, building orientation, massing, landscaping and materials which conserve energy and other resources, and which minimise risks from the impacts of climate change including overheating

Nature: Incorporate and/or connect to a network of high quality, accessible, multifunctional green infrastructure to provide opportunities for recreation and healthy living, strengthen habitats, improve climate resilience and improve air and water quality. This should include maintaining and enhancing tree cover and incorporating sustainable drainage systems in accordance with policies NE3 and F8

Movement: Provide transport infrastructure and choices which support the design vision for the site, provide good connections to the wider settlement (or those nearby), and prioritise walking, wheeling, cycling and public transport

Built Form: Use the pattern of buildings to define the arrangement of streets, squares and other spaces, promote compact forms of development to optimise the site’s potential, distinguish between public and private areas, create focal points and, where appropriate, enhance views into and out of the scheme

Public Space: Include spaces that are safe, secure, inclusive, accessible for all ages and abilities and which facilitate and encourage social interaction, play and healthy lifestyles (for example by providing high quality, clear and legible pedestrian and cycle routes, a variety of recreational spaces and places to meet, and making building entrances and windows face onto streets and other public spaces to provide natural surveillance)

Identity: Create visually attractive, distinctive and characterful development to establish or maintain a strong sense of place and pride, including through the use of a coherent palette of materials, design features and planting.

Development proposals that are not well designed should be refused, when assessed against this policy and local design policies, guides, codes and masterplans set out in the development plan. Substantial weight should be given to compliance with these policies when assessing the design quality of proposals.

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238