Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Co-housing revives something that once came naturally: Neighbourly living

While still a rarity in the UK, co-housing could play an important role in the drive to build more housing, writes Harriet Saddington

Harriet Saddington is an architect and writer, who works with micro to large architecture practices and developers, helping them to shape

......Co-housing, not co-living. With so many “cos” around, it’s easy to confuse the two, but the distinction here matters. As Sam Goss, founding director of Barefoot Architects, puts it: “With co-housing you have your cake and you eat it.” Where co-living trades private space for shared amenities, co-housing gives you both – a private home plus shared facilities, such as gardens, workshops and dining rooms – within a community that you help design and manage.

The term “co-housing” was coined in Denmark in the 1970s, reviving something that once came naturally: neighbourly living. Today it must be intentional, and most schemes typically comprise 20 to 50 homes planned collectively.

So, can the UK make co-housing mainstream? Or are we destined to keep looking to northern Europe for inspiration on how to live together well?

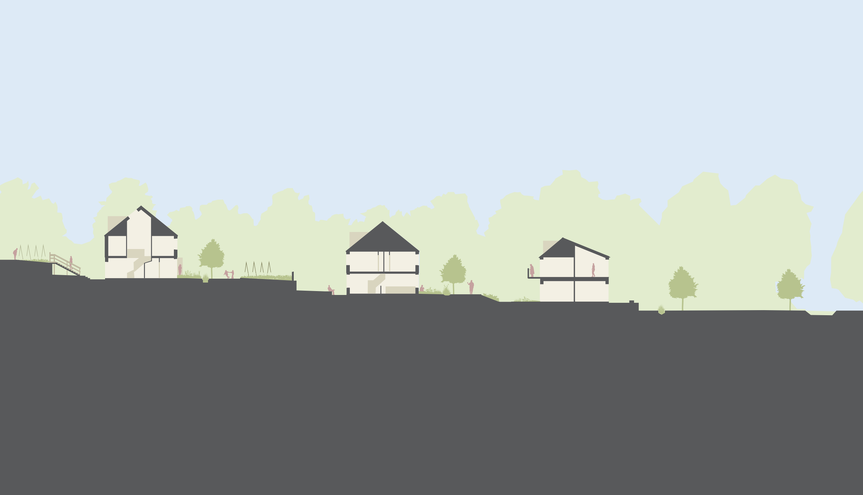

Co-housing’s benefits are increasingly clear: intergenerational living, reduced loneliness, resource sharing and enhanced wellbeing. Barefoot Architects was responsible for the UK’s largest co-housing scheme: Hazelmead Bridport Co-housing in Bridport, Dorset. The 53-home, 100 per cent affordable scheme is modest in scale, but has won multiple awards and attracts visitors from across the country.

“Why does this resonate?” asks Goss, who has been involved with Hazelmead since 2014. “Because it’s the antithesis to our consumer housing market and its exploitative financial system.”

You feel Hazelmead’s appeal the moment you arrive – car-free paths, bright homes and a genuine support network among neighbours. But the process to get there took a gruelling 15 years, endless fundraising and determined community champions. Goss calls it “slow architecture” – the kind that takes strength and patience.

So far, the UK has only 25 completed co-housing schemes, with another 14 due by 2030. Denmark, by contrast, has over 600. Nevertheless, momentum in the UK is growing, thanks to new partnerships between developers, housing associations and local groups.

For years, co-housing relied on grassroots groups. Now, major developers are stepping up. Hill Group has formed a joint venture with TOWN (the team behind Cambridge’s Marmalade Lane 2018 co-housing scheme), Its first co-housing project is at Northstowe, north-west of Cambridge. Elsewhere TOWN is partnering with The Crown Estate on a co-housing scheme in Hemel Hempstead and with Urban Splash and Igloo at Liverpool’s Festival Gardens.

Co-housing has been vaguely on recent governments’ radars for a while. The 2021 Bacon Review called for a dedicated Homes England unit to boost self-build and custom housing, which includes co-housing. That led to the creation of the Self-Commissioned Homes Unit, led by Angela Doran. “Co-housing is a form of self and custom build,” she says. “End users are designing what they want, for an intentional community.”

But perhaps within this wider label of “self and custom build”, co-housing is less appealing to large developers and strategic sites, as well as the mainstream consumer market. Co-housing is also often muddled with community land trusts (CLTs) and cooperatives. The three overlap but differ in focus. With co-housing you go through a process to create a design and way of living. Cooperatives prioritise ownership, ensuring governance resides with residents. CLTs secure land for local benefit, usually led by non-resident members.

Many schemes blend these models. For example, a co-housing project may be built on CLT-owned land or have democratic cooperative ownership, which adds to the confusion but also to the potential.

At Hazelmead, half of the homes are for social rent through a housing association partner, Bournemouth Churches Housing Association (BCHA), while the other half are offered under shared ownership with either BCHA or Bridport Co-housing, a community benefit society.

Speak to anyone involved in co-housing and they will mention the same challenges: land, funding and permission. To this, Goss adds another: expertise. Successful projects have so far needed “community champions” to drive the process. Partnerships with developers that understand the co-housing model will help strengthen and accelerate co-housing.

Within Homes England, there is tension between supporting small-scale co-housing models and the pressure to deliver at scale. But policy levers are emerging, notably the “percentage policy” advocated by the Right to Build Taskforce. This requires a portion of new developments – often 5 per cent, sometimes up to 50 per cent – to be set aside as serviced plots for self or custom-build homes. Grouping those plots together rather than scattering them opens the door for co-housing. York, for instance, is exploring high-density urban co-housing as part of its policy targets.

At Northstowe, a 10,000-home development, Homes England allocated two parcels to co-housing: one led by TOWN and Hill Group, and one by TOWN in partnership with an existing Buddhist group, Suvana. “Northstowe isn’t a one-off,” says Doran. “We are going to have more of these percentage policies so we need to get aligned to them.”

Though co-housing will make up only 1 per cent of the total homes at Northstowe, its impact is likely be greater. Co-housing communities establish life early, creating social infrastructure, shared facilities and a sense of place before a neighbourhood is fully formed.

The UK Cohousing Network promotes awareness of co-housing and supports the development of new co-housing communities. Its chief executive Owen Jarvis puts it simply: “We’re used to glossy showrooms of individual homes on new sites, but imagine, in exchange for a discount, a co-housing plot as the showroom for the community we want to see on a new development, setting the tone and culture early on of things to come – co-housing as a first rather than final thought for developments.”

The New Town Taskforce report recently endorsed co-housing under the community-led housing umbrella. The UK Cohousing Network is lobbying ministers for more recognition, proposing that every new town and town extension should include co-housing as part of a balanced mix. Without this, it warns, these sweeping developments risk becoming more of the same: a speculative, homogeneous sprawl.

New Ground in north London is the UK’s first senior women’s co-housing project, and was facilitated by PTE Architects. Here, co-housing successfully supports a distinct group of people with shared purpose. But co-housing does not require an exclusive demographic. At Hazelmead, the co-housing group had to restrict the number of people joining who were aged over 50 to ensure a diverse intergenerational community (which now spans from four weeks to 80 years old). On my visit I hear of the joy of a 72-year-old resident invited to a neighbour’s 15th birthday party.

“People said, ‘Oh you’re moving into a commune,’” says resident Kulbir, who moved with her two children from Shepherd’s Bush in London. “And then they get here and are blown away by the positives. It makes so much sense. I don’t know any other children who have this level of freedom and that intergenerational relationship.”

TOWN sees huge latent demand: People who want this type of community living, but don’t yet know that co-housing exists. It is confident that future buyers will join at various stages – some at inception, others after planning or construction. Hazelmead requires a six-month membership before commitment, a mutual check to ensure the right fit. “For an intentional community, you can’t just take people off a housing list and hope they’ll work together,” says Doran.

As co-housing matures, its “product” is becoming more recognisable: car-free streets, common houses, tool libraries, shared gardens … The challenge is to make the process faster, simpler and more accessible without losing authenticity.

“Part of making co-housing more mainstream and scalable is recognising that lots of people don’t want and frankly haven’t got the time to suffer for their art,” says TOWN director Neil Murphy. “They just want a better house in a place that offers them and their kids a better way of living than they can buy from another housebuilder.”

Research by Dr Tom Archer and Dr Lindsey McCarthy of Sheffield Hallam University challenges the assumption that community-led housing is inherently slower than conventional development. Their studies show that a fair comparison must include the lengthy land-acquisition phases typical of private developers, factors often overlooked.

Money remains the toughest barrier. Denmark’s co-housing boom in the 1970s and 80s was fuelled by government-backed, low-interest loans. When those ended, co-housing skewed toward wealthier groups, not because co-housing is inherently elitist, Jarvis stresses, but because the finance structures changed. If we want co-housing to be open, inclusive and affordable then it needs support and subsidy.

In the UK, because co-housing is an unknown entity, lending is constrained. “In both the public and private sectors,” says Murphy, “there is still a perception that co-housing is unusual and hard to place – neither conventional spec developer housing nor affordable housing – and this affects perceptions and thus pricing of risk.

“Valuers tend to see the things that actually make people pay a premium for co-housing, such as better design and sustainability standards or shared facilities, as harming rather than enhancing value and market appeal.”

Funding for shared spaces is another hurdle; grant funding covers homes, not common houses. At Hazelmead, the residents are still self-building theirs. Yet these spaces are not optional extras but essentials – the neutral glue that makes co-housing work.

Homes England acknowledges it needs to be more flexible on this, for example, looking at discounted land sales and funding models with wider affordable options.

Co-housing often wins public support, even when planners are sceptical. Goss recalls cases where planning officers recommend schemes for refusal (due to local policy making no mention of co-housing) only for local councillors to approve them at planning committee when they hear strong community backing. “Planning protects the worst but prevents the best,” Goss says, arguing that co-housing actually de-risks development. “You’re not selling off plan, you’re selling before plan,” he says. “Essentially you’ve got a group of people saying ‘I want to live like that’ before anything’s been done.”

Because residents co-design their homes, co-housing pushes quality that matters. At Hazelmead, residents insisted on 2.4m-high ceilings, large windows, and acoustic insulation to Scottish standards. Dining tables were put at the front of the house because that’s where people linger and connect.

But it’s the way elements are brought together that shapes the place, creating both an immediate and lasting impression when you visit. Benches are built into front porches; the sloping site means that fronts and backs of homes don’t stare directly at each other; pathways curve gently so there’s variety and changing sightlines; and food-growing areas line shared paths rather than being tucked way. Balancing privacy with communal generosity, the design encourages “conviviality” – a quality increasingly recognised as vital to human wellbeing.

Resident Judith confirms: “Living here has made me more conscious of the richness of human connections, no matter how small or significant they are. A smile, a hello, nurtures me.”

Operationally the community has established “sociocratic circles” (such as building and maintenance, communications, finance, environment) that draw on residents’ skills and interests, providing structure for how they contribute to the community (typically around two hours a week). Neighbours speak naturally of informal support: shared school lifts, bulk food deliveries, even nurses on call.

Co-housing aligns naturally with climate goals: shared transport, collective battery storage, food growing and net-zero operation. Its social and environmental value is measurable and personal. Residents describe new-found confidence from taking part in collective action. One resident described how they’d been promoted at work, crediting their co-housing experience for their increased sense of agency, teamwork and understanding of compromise.

Beyond the White Picket Fence, Savannah Fishel’s study of communal living across the US and Australia, published earlier this year, found that communal housing doesn’t require everyone to be “best friends” or think the same. But integration does need to be intentional; it doesn’t happen accidentally. The benefits of living communally are shown to improve awareness of wider society beyond their neighbourhood.

Housing associations, such as Housing 21 in Birmingham, are exploring co-housing, although some prefer a “co-housing-inspired” approach, borrowing principles such as shared spaces and participatory management without full community control. In the same way that there are Montessori-inspired nurseries, this approach could spread the benefits more widely. Purists might see it as dilution; others suggest it could seed cultural change.

A co-housing “lite” model could make community living more accessible to renters and social housing tenants. Social rent homes are included at both Hazelmead (50 per cent) and New Ground (30 per cent), showing it can work as part of a mixed-tenure model. But to make rental co-housing viable at scale, new finance tools are needed such as bridging deposits, flexible rent-to-buy models, or intermediary funds for key workers.

Diluting the model inevitably reduces its impact. Co-housing is more than just resident associations or social clubs, and the UK Cohousing Network warns that if it is oversimplified then the collective intention – combining design, governance and social practice – may be lost. Evidence from Sweden highlights problems in schemes established by developers who recruit residents afterwards.

Co-housing advocates emphasise that there is a science to how a scheme’s design shapes its lived experience. For instance, if the common house appears too institutional, it tends to go unused. Likewise, having a nucleus of early-adopter co-housing enthusiasts is essential to sustaining the collective spirit, both before and after the involvement of facilitating developers. Ultimately, the model cannot simply be appropriated into the mainstream or mass-produced for profit.

For co-housing to thrive in the UK– more than just scale – it needs legal and policy recognition, market distinction, increasing evidence of its standout social and environmental benefits, and perhaps design standards too.

The UK Cohousing Network is set to release a paper for ministers suggesting that, with solid support, up to 15,000 co-housing homes could be delivered over the coming decades. But scale isn’t the only measure that matters. Co-housing’s real value lies in what it represents: citizen-led design, neighbourliness and a sense of shared purpose.

As Jarvis puts it: “We should treat housing like ecosystems; neighbourhoods not units. Try imagining the government’s targets as 50,000 neighbourhoods of 30 homes each. Co-housing is a concentrated dose of good neighbourhood design – shared space, trust, belonging.”

Given the state of our housing system, perhaps the better question is why co-housing still needs to be justified. By centring citizen needs, co-housing not only serves its residents but raises the standard for everyone.

Harriet Saddington is a writer and architect with a background degree in architectural history who works with architecture practices and developers with a focus on social impact

This article first appeared in The Developer magazine, Winter 2025 – order the print edition

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238