Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Design by AI: Why we need to hack the algorithm

Amid dystopian predictions, the fact that AI tends towards the typical, standard and normative doesn’t sound so bad – but applied to systems like the built environment, that’s dangerous

Wait five minutes and someone will tell you the latest thing they’ve outsourced to AI; How it’s taking minutes of meetings or summarising reports they haven’t read.

It’s hard to say for sure, but I suspect AI is also filling my inbox with platitude-laden epistles and op-eds. Suddenly everyone is a writer. Whack in a prompt and off ChatGPT goes, generating line after line of wooden prose or non-sequitur waffle. Why use one word when you can use 26 and still say nothing interesting?

Earthlings, I can’t edit this way. At least bad writing used to have flavour. It used to touch grass. Now it’s autotuned.

But wait, you say, AI will get smarter. It will take your job! Fine. But will it stop being boring?

According to Dr Jutta Treviranus, director and founder of the Inclusive Design Research Centre in Toronto, the answer is, well, concerning: Unless we do something fundamental about how it works, the output of AI will be average.

“AI systems are making everything better for people who are already doing fairly well and worse for anyone who is outside that threshold of average”

Treviranus has been studying AI and machine learning since the early days of the internet. At the institute, her mission is to ensure emerging technology and processes are designed to be inclusive. She’s also a professor at OCAD University, a school of art and design.

“When it comes to AI bias, most people say all we need to do is make these systems smarter by giving them more data – that the reason for mistakes is that the systems don’t have enough accurate data about particular scenarios,” says Treviranus in an interview for The Developer Podcast.

“When we’re using statistical replicators, they are making decisions based on statistics, so they look for the statistical average and use predictive analytics to decide the best thing to do.”

That’s why the output is so mediocre – if 80% of the writing that ChatGPT has been trained on is passable and only 20% extraordinary, the model will predict the most typical next word, which is also likely to be the most average word, regardless of the quantity of data it’s fed.

Of all the possible dystopian predictions, the fact that AI tends towards the typical, standard and normative doesn’t sound so bad – except that when applied to systems including the built environment, it’s dangerous.

“What people don’t seem to recognise is that for people who are outliers – who are minorities outside of the statistical average – the systems will always decide against them.”

Love what we do? Please consider supporting us as a member to keep our content free, inclusive and challenging.

Who is an outlier? We all are, at one point or another: when pregnant, have laser eye surgery or otherwise stray from the mean.

“Almost all of us at some point, especially when we’re struggling, especially when we need good design and don’t have the capacity at the time to adapt, are going to have needs that diverge from that middle.”

We also live in a world of polycrises, with extreme weather events that, although increasing in frequency, will never be average.

But there are ways to challenge this thinking and the logic that underpins AI – after all, it is just doing what we’ve been doing: Design using one-size-fits-all standards for average-sized humans who behave in preset ways all the time.

In short, we design for people who do not, in fact, exist.

Changing AI means changing the way we work – rethinking the way we design, process and categorise information.

Unlearning this means abandoning majority rules thinking, says Treviranus. It means designing for the edges in ways that still serve the centre. It means installing that drinking fountain lower to the ground, because the majority – the able-bodied – can bend down.

“Even in a democratic system, where you’re using majority rules voting without considering human rights or the actual needs of people at the edge, the trivial rules of the majority will always outweigh the critical needs of the few,” says Treviranus.

“AI is automating, amplifying and accelerating patterns of disparity and fragmentation”

“The same thing happens with design thinking, because you’re using a voting process where the majority of the sticky notes – the single solution that is going to have the highest impact on the most number of people – is the thing that’s selected.”

Treviranus refers to that classic design-thinking squiggle that resolves into a single line. “What you’re doing is winnowing down the choices to a single solution where there are winners and losers, and the losers tend to be the people we work with.”

That’s what AI is doing at speed – hyper gross over-simplication: “AI is automating, amplifying and accelerating patterns of disparity and fragmentation,” says Treviranus. “There are really critical reasons why outliers are so important.”

“AI systems are making everything better for people who are already doing fairly well and worse for anyone who is outside that threshold of average,” Treviranus explains.

But Treviranus has developed an alternative design approach – one she calls the “virtuous tornado”.

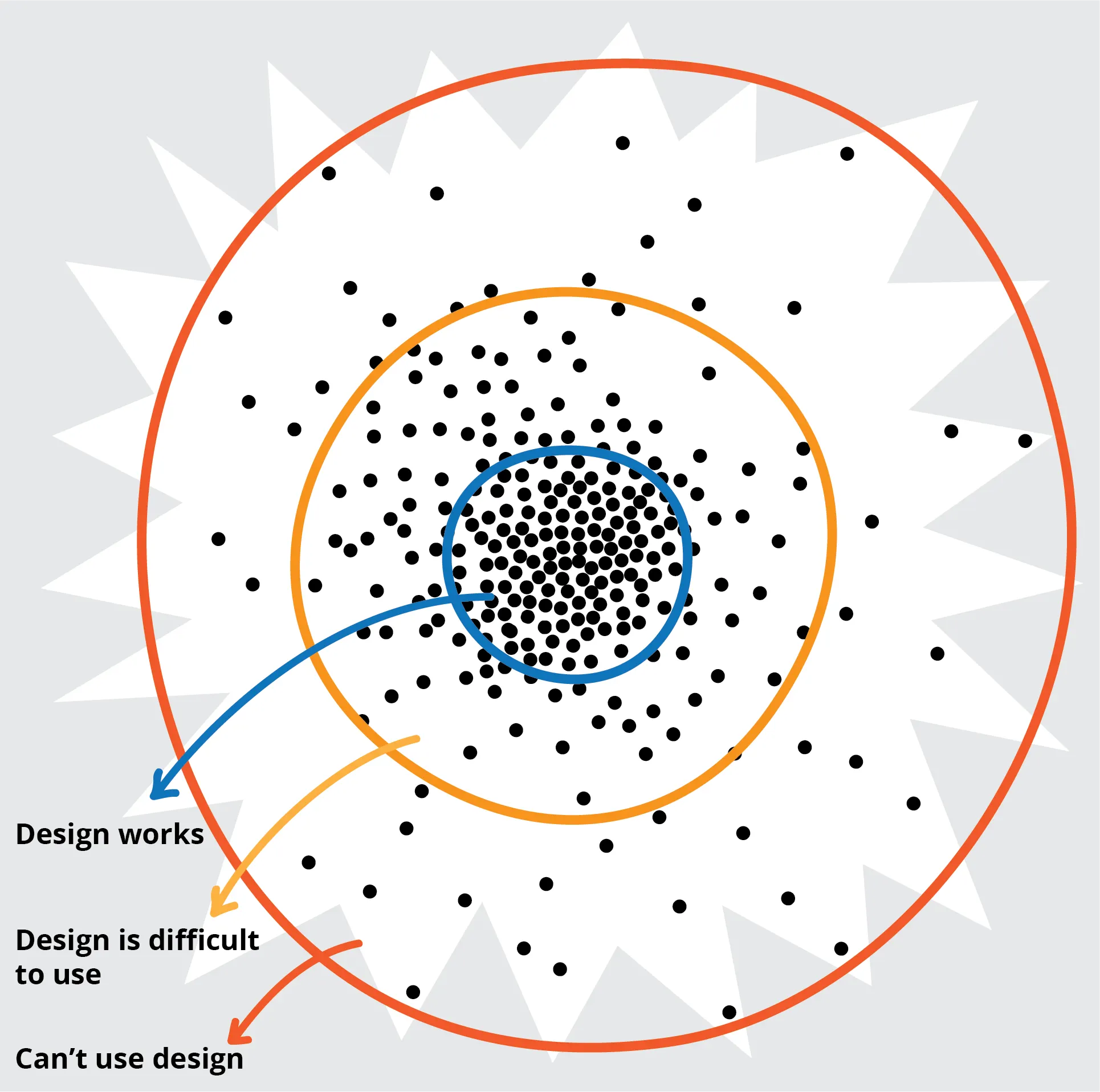

Using the data she’s been collecting on what individuals need to thrive, Treviranus has plotted these points on a model to illustrate the data. The result is what she calls her “human starburst” – it shows 80% of the needs clustered in the central 20% of the space, and the remaining 20% spread out.

What if the starting point of design is not the average, but the extreme?

“If we only design for that central middle 20% and 80% of the needs, then as our world changes, we are not sufficiently adaptable.”

“It is out at that edge that we find the innovation, because it isn’t the complacent middle that needs change and can come up with innovative ideas,” she adds.

“If we design with people who have lived experience of struggle and the need for resourcefulness on a daily basis, then we are going to create systems that work for us when we’re struggling and it will give us all room for change.”

This turns majority rules thinking on its head, where the starting point is not the average, but the extreme: “We try to find the people that are not able to use our systems at all, or have difficulty using our systems, and we try to design with them in such a way that we can evaluate and test it in multiple iterations.”

“We try to encompass as many of the needs as we can within this system, and at each iteration we ask, ‘Who are we still missing? Who are these design decisions excluding?’ And then we bring those individuals into the design process and expand the design.”

“We’re trying to stretch the system as far out to those outer edges as possible because that makes us future ready. We’re all going to face crises. We’ve created a world at the moment where it’s crisis upon crisis. Things are changing so quickly, we need to be adaptive in order to survive, so we need our systems to be as adaptive as possible.”

“If we’re wanting innovation and risk detection, which I think is what we need right now, then the vital few are the outliers”

This is applied to testing existing masterplans: “We’ll ask what would be the most catastrophic thing that could happen or the most unexpected and let’s run through that,” says Treviranus.

This stress test ensures the design is able to address emergencies and disasters – or smaller unexpected events, such as a big paralympic event at a stadium that results in a higher percentage of wheelchairs attending an event than anticipated.

“That’s the other positive thing that happens when you consider outliers. Frequently we come up with really innovative and interesting new ways of dealing with things.”

“It is the people who have needs out at the outer edge that are going to give us ideas about how to create a much more flexible system for when our [current] systems all of a sudden don’t work for us anymore.”

Treviranus describes a wayfinding system they developed for the partially sighted which ended up being used by everyone visiting the building, “The positive comments came from everyone, not just people using canes.”

Another example is how the deaf community developed the technology for texting and video calls long before mobile phones and video conferencing. Or how mobility scooters developed for people with accessibility issues evolved into e-scooters and e-bikes for the masses. And these are just a handful of examples of how technology developed for the few now serves the many.

“Creating communities is going to be key to our survival”

As for AI, Treviranus has experimented with reversing or inverting the algorithm to use AI to search for outliers rather than the average.

Her team looked at employment systems that take a profile of a successful employee and scan candidates to replicate that. “Of course, replicating means you’re creating a monoculture… so we reverse the algorithm so that it’s data exploration: What are the missing perspectives that we need within this pool of applicants?”

“That creates a more adaptive, much more diverse team so you have further choices on which ways to pivot. We tried it for academic admissions and other places where you are choosing from a large pool, but it can be used in other ways.”

In design, Treviranus suggests an inverted algorithm for AI could be used to come up with other choices or options, or to think up scenarios where the design falls short.

“There are so many things that have become integrated into our mindset and we no longer question… but if we’re wanting innovation and risk detection, which I think is what we need right now, then the vital few are those 20% that are the outliers.”

Treviranus explains that human leaps of progress typically happen when humans are relaxed and free to make diverse and complex choices. “The key to that is the opportunity for collaboration and symbiosis and working together. When there are pressures of crises or the threat to survival… if you have already established relationships with others… you are more likely to survive.”

“Creating those types of communities is going to be the key to our survival,” adds Treviranus. “Reaching across diversity, finding people that may have dissonant views but that we can bring into a collaborative relationship or a collective community is the best strategy that we have.”

After speaking with Treviranus, the use of AI even for mundane tasks feels problematic.

Take those minutes from your video call: Sure, AI has recorded the key takeaways and reduced the conversation to a list of actions. But what about that one radical insight the intern shared in passing?

Oh. Nobody wrote it down.

Listen to the podcast to hear the full conversation and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. Sign up to The Developer Weekly email to find out when new episodes of The Developer Podcast go live and more.

Sign up to The Developer Weekly email to find out when new episodes of The Developer Podcast go live. You can get episodes early and our magazine when you support our podcast on Patreon at www.patreon.com/thedeveloperuk

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238