Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Urban sacrifice zones: Where deprivation and high pollution intersect, citizen health is vulnerable

This report by the Urban Health Council proposes how communities might hold industrial polluters to account for their damage. All maps courtesy of the Urban Health Council.

The working Wikipedia definition of a sacrifice zone is a geographic area that has been permanently impaired by environmental damage or economic disinvestment. However, such an expansive and non-specific definition causes two problems: firstly, it allows for legal disputes over what is meant by "impaired" and "permanently"; secondly, it means that policy and legality are only concerned when the bad thing is an extreme case. This leaves communities unable to seek justice at those first instances of poor health outcomes.

We propose the use of geospatial and physiological data to create a more specific working definition of "urban sacrifice zones”, one that will allow communities to hold industrial polluters accountable at "first harm" or as close to "first harm" as possible. Adapted from the work of Dr Max Liboiron, the "right to pollute" was coined by Centric Lab to describe the legal rights given to industrial polluters to contaminate soil, water and air.

There are no safe levels of pollutants, only an epistemology that prefers to question how much something can be pushed before it breaks down

In their work Pollution is Colonialism, Liboiron identifies the mechanics of a permission-to-pollute system as follows: "A core scientific achievement in the permission-to-pollute system was the articulation of assimilative capacity - the theory that environments can handle a specific amount of contaminant before harm occurs.”

There are no safe levels of pollutants, only an epistemology that prefers to question how much something can be pushed before it breaks down earlier than how to optimise life - nature and human.

Health is ecological, meaning that it is influenced by our body’s interactions with the environments in which we live - from microorganisms in natural spaces orchestrating the human gut, to the quality of air that our lungs are ingesting for the function of our organs. It must be acknowledged that both the quality of our external microbiome and air is driven by systemic governance, such as "right to pollute" policies that allow land, water and air to be contaminated.

However, this ecological view is often erased by the more popular "individualised health" narrative, which centres responsibility on the person. We go to the GP as an individual to seek care for a particular ailment, be it a cough, headache or localised pain. The usual practice is that we are given specific treatment and sent on our way. Even when a person returns with a progression of the original ailment, the place where a person lives is seldom taken into consideration.

Additionally, there is an abundance of medical practice, literature and campaigning related to improving health outcomes by changing behaviours (what people eat and how much they move). While these two factors are important, they are not the full ecological picture. As part of a continual series bringing light to the industrial systems that operate around us and the political and place-based determinants of health, we are exploring the intersection between two areas of politicised industrialisation that lead to "environmental damage or economic disinvestment" - the abundance of emissions sources in an area against the levels of deprivation.

The word "politicised" is intentionally used here to refer to conscious decisions made by those who hold political office. An area that remains deprived over time is symptomatic of a lack of investment from the governing powers; an area that has sources of emissions is legally protected and allowed to exist because political decision-making considers it acceptable. These are the places deemed as acceptable to sacrifice in the name of wider economic development.

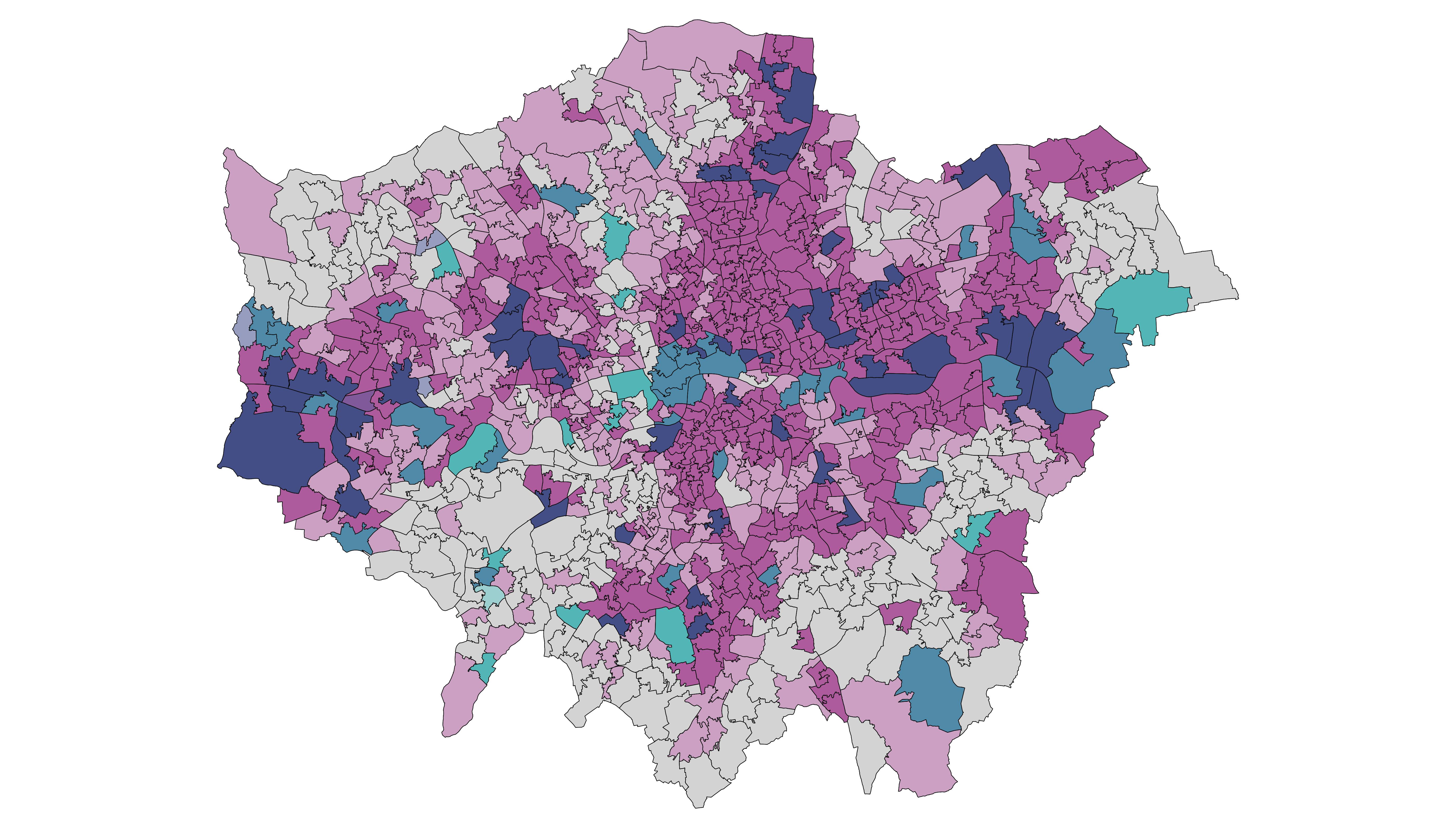

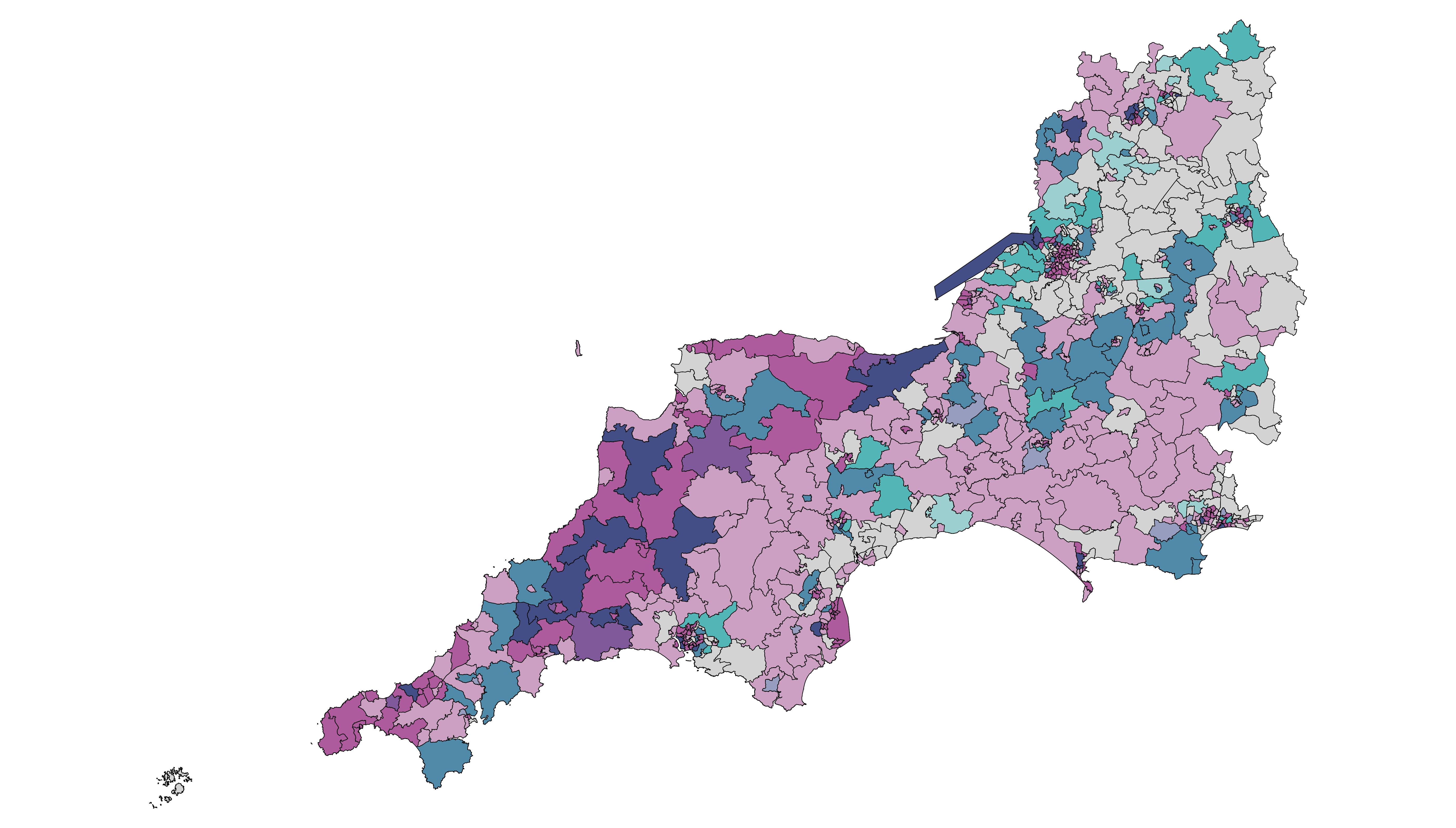

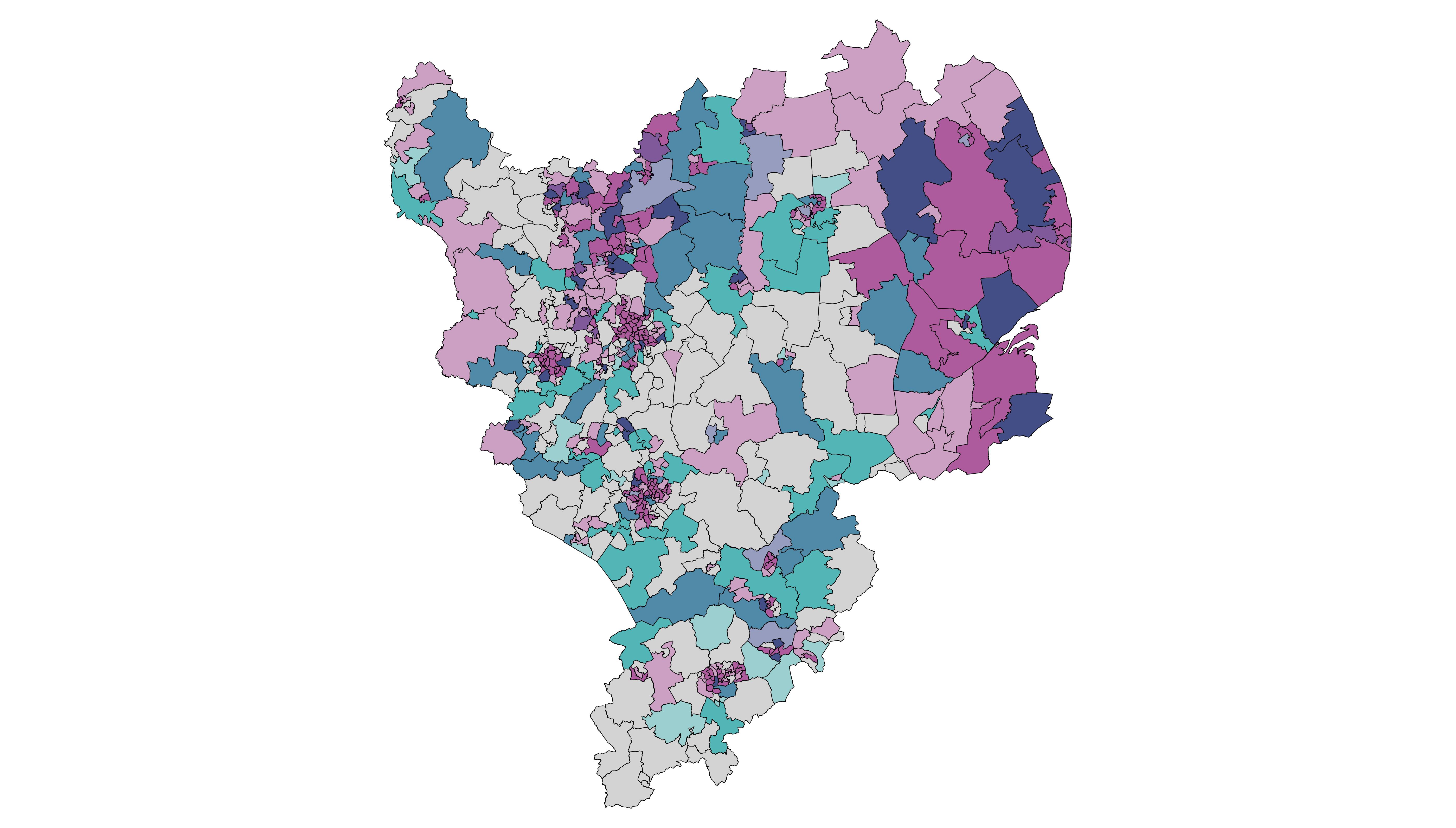

To demonstrate the number of emissions sources in an area with the right to pollute, we accessed data from the UK National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (NAEI) and plotted the points on to a map through the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS). We then organised the data by which NHS Middle Layer Super Output Area (MSOA) geographic boundary the point fell within, and totalled up the amounts. This allowed us to match this data with the ONS Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 data.

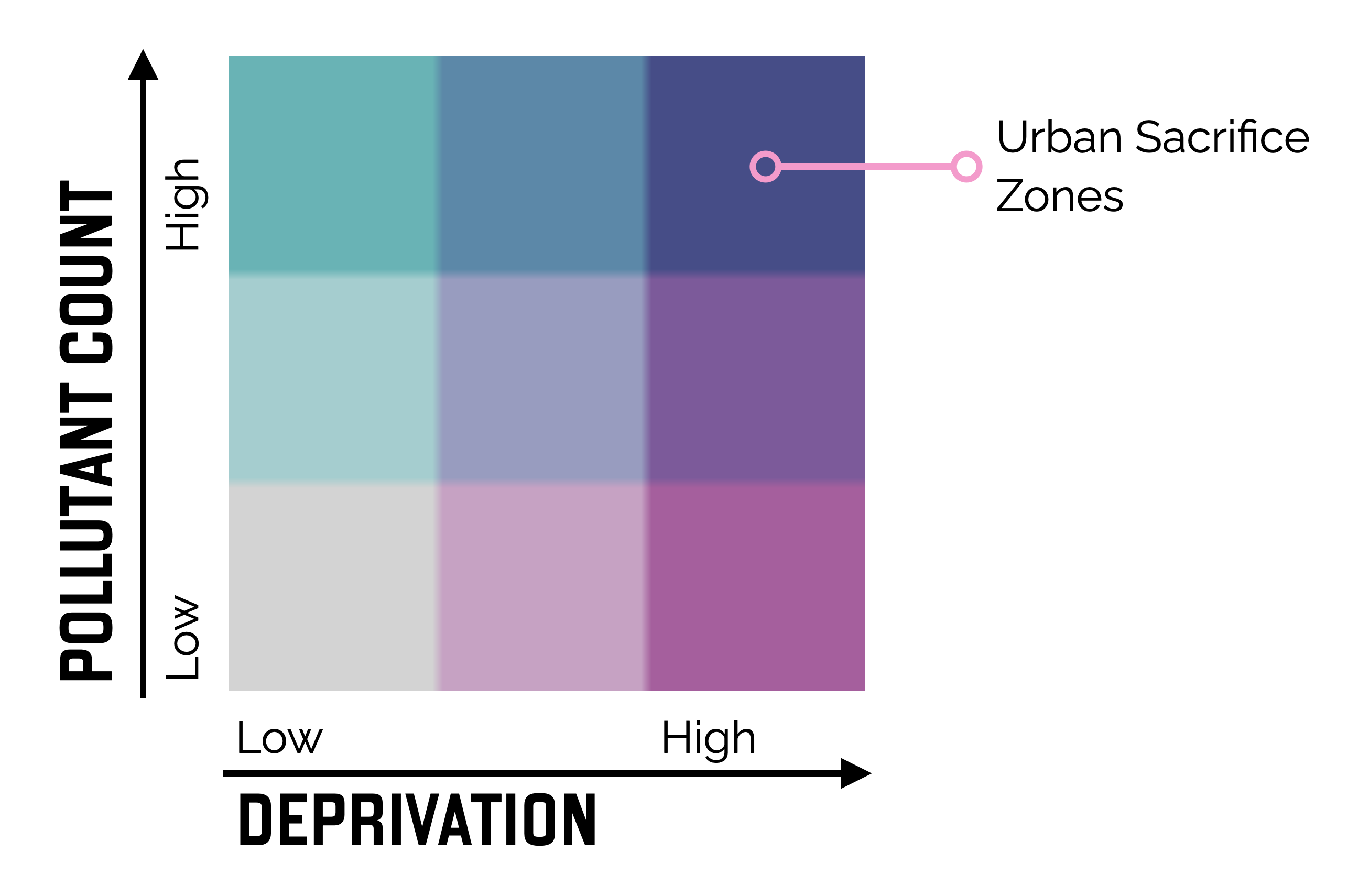

We chose MSOA level data as this small area represents a more personalised association to place. Using OGIS we created a series of bivariate colour maps that help show the various intersections. We created a high/medium/low for each metric in order for the scale to work. The Index of Multiple Deprivation runs from a value of 10 and is relatively consistent in the numbers spread across the range.

There is no linear relationship between location and polluter.... This brings up the key proposition: why is pollution an accepted element of organised society?

For the NAEI data, due to the imbalance of a significant number of areas counting less than 1, we created a custom scale. When creating an equal interval scale it resulted in the medium range having values of between 120-240 emissions sources.

While this is a medium value from the dataset, it does not represent a medium value in qualitative or colloquial terms. "Medium" tends to mean "okay, but not great”, however, a location that has nearly 240 sites or emissions is high, certainly when you reflect that there are a handful of sites in those values. Therefore, we set the "low" value as below the average, the "medium" value as twice the average, and the "high" value as anything above that. This is an executive decision in order to ensure that the areas of extremely high value are not lost in the data.

There is no linear relationship between location and polluter. A correlation test showed there is no direct relationship to infer any intention between areas of deprivation and a focus on putting sources of pollutants in those locations. The northwest and southeast have the highest values - most likely because they are some of the most populated regions in England. This brings up the key proposition: why is pollution an accepted element of organised society?

There are a high number of MSOA regions that have high numbers of polluters and high deprivation. However, pollution does not appear to discriminate absolutely; there are areas where deprivation is low (indicating areas of relative wealth) with high levels of pollutant count. Pollution comes for us all, just faster for some than others.

The data and hotspots presented in this report give researchers, campaigners and communities alike the opportunity to identify areas for further investigation. The hotspot findings can contribute to the scientific, political and social understanding of sacrifice zones in the larger investigation on the right to pollute.

These sites have been given the right to pollute the air we breathe and the environment around us. The historic engineering term of "assimilative capacity", which was developed to legitimise the polluting of a natural body of water, has underpinned the epistemology of industrial capitalism: privatise the gains, socialise the risks. These risks have grown too great and only by stopping the right to pollute will we (a) reduce health risks but also (b) stem the dysregulation of planetary systems leading to climate change.

An excerpt from The Urban Sacrifice Zones and the Right to Pollute, a report by Urban Health Council. Lead Author: Josh Artus; editor: Daniel Akinola-Odusola, MSc Neuroscience; editor: Araceli Camargo, MSc Neuroscience. Read the full report on the Urban Health Council website.

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238