Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Small playground, big ideas: making space for play

With rising land values, playground space is at a premium. Clementine Wallop reports on how London primary schools are coping

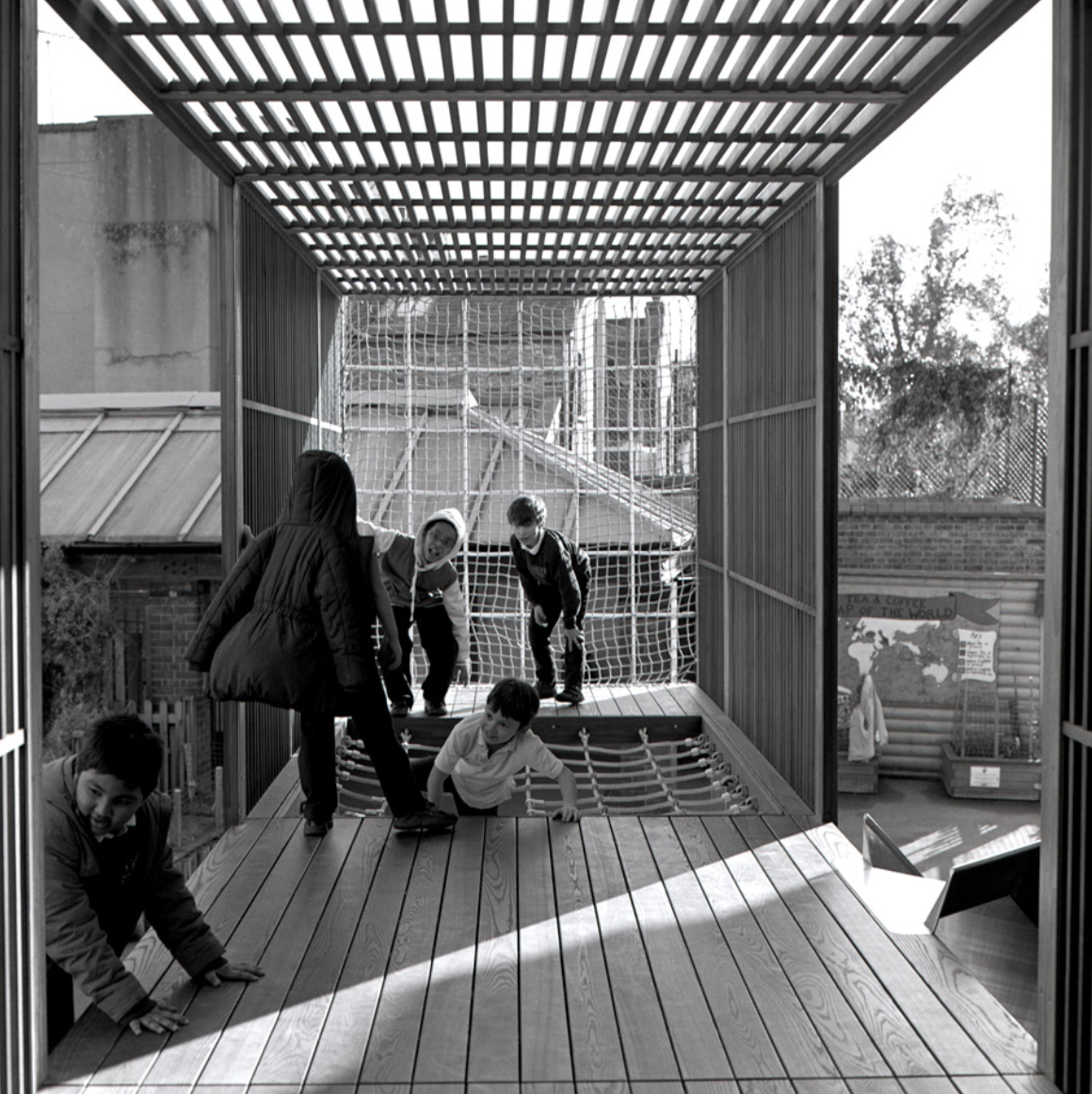

It is playtime at Chisenhale Primary School in Tower Hamlets, London. Children are running, jumping and laughing. They are on the tarmac, but also swinging from and exploring inside and sliding down a structure they know as Chisenhill: a project by architect (and school parent) Asif Khan.

Chisenhale’s main building is Victorian, its site bordered by streets and houses; the school can’t move further out. When it wanted more playground space, the solution was to extend upwards with a two-storey play area. Its long shape echoes the school building, while the design adds excitement and originality.

Chisenhill is the school’s answer to a problem facing many London primary schools: they want more play space for their pupils, but their sites and their budgets don’t allow for expansions. Funding shortages, fast-rising land values and heavy-handed risk management add to the challenge of finding ways for more children to play in less space while providing the challenging, adventurous play essential for child development.

Much of the evidence in London is anecdotal rather than data driven, but Tes (formerly Times Educational Supplement) research from 2014 showed pupils in a third of expanding English primary schools would have less space to play due to a rising birth rate and existing playground space being taken up by new classrooms.

“A combination of factors including the need to accommodate pupil numbers, falling school budgets, and rising land values make it easy to see why schools might be tempted to build on playground land or sell off playing fields to plug holes in their budget,” says Fiona Sutherland, deputy director and head of communications at charity London Play, which aims to get children in the city playing outside more often.

“A combination of factors including rising land values makes it easy to see why schools might build on playground land or sell off playing fields”

“Add to this the rise of free schools and academies, which are able to set their own rules on space, and the gradual shrinkage of school playgrounds starts to look like an inevitability.”

As schools face this battery of challenges, rooftop playgrounds are becoming more common, site-confined schools are seeking bespoke play equipment to suit narrow spots, and indoor play spaces are becoming bigger and more ambitious.

At Holy Trinity Primary School in Dalston, the double-height play deck on the second floor, completed in 2016 by Rock Townsend, provides play space the school couldn’t find elsewhere on an especially tight site. The play deck sits sandwiched between the school classrooms on the ground and first floor and 101 new flats above. Describing the project on its website, Rock Townsend says the doubling of pupil numbers and squeezed funding for the project led to this solution.

The search for more space comes as teachers and play experts recognise the damage heavy-handed risk management can do to children’s development, especially when space is limited

At Sarum House School in Hampstead, architect Square Feet designed a multi-storey structure that looks like a small cottage, with a slide coming down from its front door. The rooms in the cottage are a popular play space, but also provide teaching areas. The same play area features a row of rainbow-coloured beach huts for PE storage.

The search for more space comes as teachers and play experts recognise the damage heavy-handed risk management can do to children’s development, especially when space is limited.

Stories about schools that have banned running, football, and what one source mysteriously called “boisterous play”, are common.

Teachers have said parents demand schools keep their children away from water play, even in shallow playground stream features, or from sand that might dirty shoes and clothes. In such environments, independence is limited, and prohibition is far more common than permission. The prevailing atmosphere is one of caution rather than creativity.

“Play spaces that are too small do cause restrictions to the variety of activities that are possible,” says Nicola Butler, chair of Play England. “For some children football at break time is the highlight of their day at school, so if other activities like running are banned then it is impossible for some children to let off steam.”

Stories about schools that have banned running, football, and what one source called “boisterous play”, are common

At Chisenhale, training and an acceptance of the importance of risk is key, says Ruth Crossan, parent engagement and extended schools manager: “We wanted the children to have enough to do that wasn’t just ball games, and there weren’t enough different spaces for that. We wanted something inspiring and challenging for children.”

“We do very careful and thorough training of playground staff. When we first got [Chisenhill] we only let certain age groups play at certain times of day because they were so excited and so many children were on it. Now it’s less of a novelty.” says Crossan.

“We are quite firm with parents that physical play is an important part of education, and some of these children don’t get many opportunities for physical activities. They aren’t necessarily going to go out and learn how to climb a tree,” Crossan says.

In addition to its new structure, Chisenhale has a rooftop space featuring raised flower beds, where children grow herbs, crops (on a miniature scale) and vegetables. On the way to the rooftop, there is a beehive. The school is committed to ensuring its outside space feels as green as possible within its urban setting.

“What we want to say with the playground is that we are a school that invests in more than just lessons”

A lack of space doesn’t have to mean a lack of imagination, says Oliver Woodward, headteacher of Columbia Primary School, whose school is seconds from fashionable restaurants and vegan cafes in London’s Bethnal Green.

When he first became headteacher six years ago, there was almost nothing in the playground, Woodward says.

Since he took over, he has spent around £120,000 overhauling the space, which is now home to two bespoke structures by Adventure Playground Engineers and Erect Architecture, the practice behind the Tumbling Bay playground in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

Known to Columbia pupils as the Big Structure and the New Structure, they grow like trees from the playground surface, responding to the branches of Ravenscroft Park waving from over the school wall.

“A school playground will be used very intensively for a short period of time every day, which is completely different from a playground in a housing estate”

“With 430 kids, we are one of the schools with the littlest playground size to pupil numbers. What we want to say with the playground is perhaps that we are a school that invests in more than just lessons,” Woodward says.

“I want my school to be designed as carefully and thoughtfully as my home, partly because I spend more time in my school. The look and feel of the school is vital.”

Erect’s work is designed to encourage creative as well as physical play, says Barbara Kaucky, founding director. She acknowledges the difficulties small playgrounds can present, but doesn’t believe they should limit children’s activities.

“When you’re designing for a school playground, what you need to remember is that it will be very intensively used by a lot of children for a short period of time every day, which is completely different from a playground in a park or a housing estate,” says Kaucky.

“It has to be incredibly durable, and there are certain things you can never do because they just don’t offer the capacity, like a swing for example,” Kaucky adds. “We design objects that aren’t too definable, and objects that can develop with age: a challenge that might be too much in year one you could be a master of in year three.”

“I wish I had more data, but my belief is that you have fewer accidents in an interesting and engaging playground”

Contrary to what a risk-averse teacher or parent might fear, Kaucky thinks adding play equipment – whether in the form of loose parts or permanent structures – to playgrounds makes them safer.

“I wish I had more data, but my belief is that you have fewer accidents in an interesting and engaging playground,” she says.

In Columbia’s case, the structures are complemented by a PlayPod, which is a shed filled with loose parts for play. Designed by Bristol-based charity Children’s Scrapstore, PlayPods house a range of scrap materials suited to the school. This might include cardboard tubes, tyres, material, netting, ropes, crates and bins.

When The Developer visits Columbia, some children were swinging from the structures on cargo nets that had come from the PlayPod, another boy had made himself a nest in a crate, and two girls were sitting on a bench under a piece of pink velvet.

Loose-parts play allows children to use spaces in a way they might not otherwise, an advantage for a site-confined school, according to Daniel Rees-Jones, play development officer at Children’s Scrapstore.

“The PlayPod offers an opportunity for children to build and create; it offers an opportunity for more collaboration and less directional movement. Loose parts play also helps use all available spaces: edges and corners become opportunities for play. Edges become walls, and there’s use in anything you can tie off or swing on,” he says.

Loose parts play also helps use all available spaces: edges and corners become opportunities for play

There is a degree of trial and error to working with scrap in schools, but since installing the first PlayPod a decade ago, Scrapstore has shown the benefits PlayPods can bring to playgrounds, especially those struggling with behavioural challenges.

“We first started in September 2009 and we’re still learning about the length and type of scrap we can use. There are certain things that haven’t worked. To start with, we gave 2.5-metre drainpipes, but you need a five-metre radius if children are going to swing them around... we don’t give schools drainpipes any more,” Rees-Jones says.

“Play is about choice and freedom of choice. Give them a PlayPod and you have completely revolutionised that space. If you just give them tarmac, you’re going to get directional play. With scrap you get less directional play, more creation, and more reclaiming of directional spaces,” he says.

Scrapstore’s research has shown that PlayPods can help reduce accidents and incidents in schools, but this relies heavily on the co-operation and goodwill of playground staff who want to foster a more permissive environment, he says.

“Better trained school lunchtime staff and support for outdoor play from school senior management teams can make a big difference to children’s enjoyment of play time and the range of different types of play that children can experience at school,” says Play England’s Butler, citing PlayPods as one way of changing play in schools.

Scrapstore’s research has shown that PlayPods can help reduce accidents and incidents in schools

Bespoke design solutions that create flexible space allow children to better enjoy and express their preferences at play time. For Woodward, it is crucial that his pupils feel the school encourages their interests; he recently installed an area of fixed musical instruments in the playground after a group of children started a punk band.

Designing play spaces that recognise the needs of less physically confident children is also important. In tarmac-only playgrounds, which Rees-Jones says represent around a third of the playgrounds he visits, directional play such as football or ‘It’ often doesn’t leave room for children who prefer slower forms of play.

“I think [the playground] enables the children to be more inventive. It’s not just a matter of being able to play It, it’s seeing children realise they can play It up or down on the structures: it just makes play more interesting. It also offers flexibility for their own individual interests: if they’re all about climbing, they can do that. If they’d like a quiet corner to do some reading, they can have that,” Woodward says.

While teachers and play experts promote the importance of well-designed and thoughtful play spaces, they all talked about the funding constraints facing many London primaries. To want a better playground is one thing, to pay for it is another.

“The challenge is money: a lot of primary schools in London are really under the cosh”

Between 2009-10 and 2017-18, total school spending per pupil in England fell by about 8%, according to 2018 figures from the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Woodward’s situation was unusual: Columbia benefitted from National Lottery cash for its PlayPod, and he used a historic carry forward to pay for the play structures. Neither project required parent fundraising.

At Chisenhale, the play structure was a three-year fundraising project. Crossan says she believes more schools are taking steps to improve their play areas, but “the challenge is money: a lot of primary schools in London are really under the cosh.”

Khan’s original plan for the playground was more extensive but would have been too costly. Sources contacted at other London schools mentioned plans drawn up and then discarded due to funding problems, or limited to their bare bones and minimum spending.

When Erect is working with schools, there is an acceptance that the practice’s vision sometimes won’t match the available funds for some years, Kaucky says.

“All our school playground projects have struggled with cash. What we do is prepare a masterplan and then start implementing it if the money becomes available. In some cases it’s taken six to seven years to get anywhere near where the vision was. That’s how we deal with the dire funding situation.”

Still, Kaucky says wherever possible, schools should add imagination and interest to their play areas, even when funds are tight and times are hard.

“A small playground is a challenge, so you just have to make it the best playground possible,” she says. “There are certain things children can’t make up or imagine.”

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238