Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

It should be a no-brainer, so why aren’t we building more Passivhaus?

Nearly a decade ago, the adoption of Passivhaus seemed inevitable. What happened? And with looming net zero targets, will the government make the standard mandatory now? James Wilmore reports

Nearly a decade ago, things were looking rosy for the UK’s Passivhaus movement. Chris Huhne, then-energy and climate change secretary, spoke at the inaugural UK Passivhaus Conference where he branded the German eco standard a “watershed moment in our relationship with the built environment”.

The former Liberal Democrat MP, who served in the coalition government, treated his audience to some further inspiring oratory. “Passivhaus is a fundamental re-imagining of our relationship with the outdoors,” he said. “Rather than seeking to subvert nature and bend it to our will, we can enter into a symbiotic agreement.”

Nobody could accuse him of lacking ambition that day. “I would like to see every new home in the UK reach the Passivhaus standard,” he declared.

But, rather like Huhne’s career, since then Passivhaus has remained somewhat on the sidelines. Originating in Germany, the standard is designed to create air-tight buildings – often triple-glazed – which use very little energy for heating and cooling.

The UK currently has around 1,200 certified Passivhaus units, with most of these residential. Around 130 Passivhaus projects are currently under development.

Pockets of innovation have emerged across the UK. A smattering of councils have embraced the approach, some more than others, while other institutions have employed the system. The University of Leicester, for example, has what is regarded as the UK’s biggest non-residential Passivhaus building. And in Edinburgh, three schools are being built using Passivhaus principles.

Yet as the noise around climate change reaches deafening proportions, there remains a lack of uptake. In essence, it should be a no-brainer. An estimated 43% of carbon emissions in the UK are produced by occupied buildings.

So what is holding Passivhaus back? Is it fears over cost? Its complicated nature? And is there light at the end of the Passivhaus tunnel?

“People don’t understand what a high-performing home is. Nobody really understands that the homes they’re living in are unhealthy”

The main issue, in a private housebuilding sector dominated by big players, is that there is no legal obligation to build to the standard.

“The reason we are not building Passivhaus to significant numbers is there is no legislative requirement to do so,” says John Palmer, research and policy director at the Passivhaus Trust.

With the market dominated by the big house builders, there is a reluctance to take risks. “Most developers will choose to build to minimum standards,” says Palmer.

Architect Justin Bere, a Passivhaus specialist who has written a book on the subject, echoes this. “It’s very difficult for an ethical developer to do anything differently in the current climate,” he argues. “They (developers) are buying in competition with people who just want to achieve the absolute minimum in terms of acceptable quality and maximise their own profit. Where profit is king, larger developers are in a race to the bottom.”

Palmer concludes his point by saying: “If you want to see full estates worth of Passivhaus then the government needs to legislate because otherwise, the mass builders won’t do it.”

Another factor is price. Building Passivhaus costs more and demands a premium in the sale price. In this respect, those involved with the movement sound similar to those trying to make offsite manufacturing mainstream as they point to the problem of economies of scale. “You are effectively talking about a one-off product at this stage,” says Palmer. It’s been estimated that a new Passivhaus home costs around an extra £5,000 to build. But as Palmer says: “Once you get the volumes up then that extra £5,000 gets absorbed and it becomes a normal business.”

“Contractors often complain there are delays associated with Passivhaus”

The extra costs of buying will also be quickly recouped by the energy savings that are made living in Passivhaus, argues Palmer. He lives in a Passivhaus home where his annual energy bill is around £150.

General ignorance of Passivhaus among the wider public is also a problem. Passivhaus is “poorly understood”, says Palmer, and “people think it’s a hermetically sealed German box.”

This feeling that people don’t get it is shared by Emma Osmundsen, managing director of Exeter City Living, a housebuilding company wholly owned by Exeter City Council. The council is interesting in that for the past decade it has been building Passivhaus buildings, although it has still only built around 103 in that time.

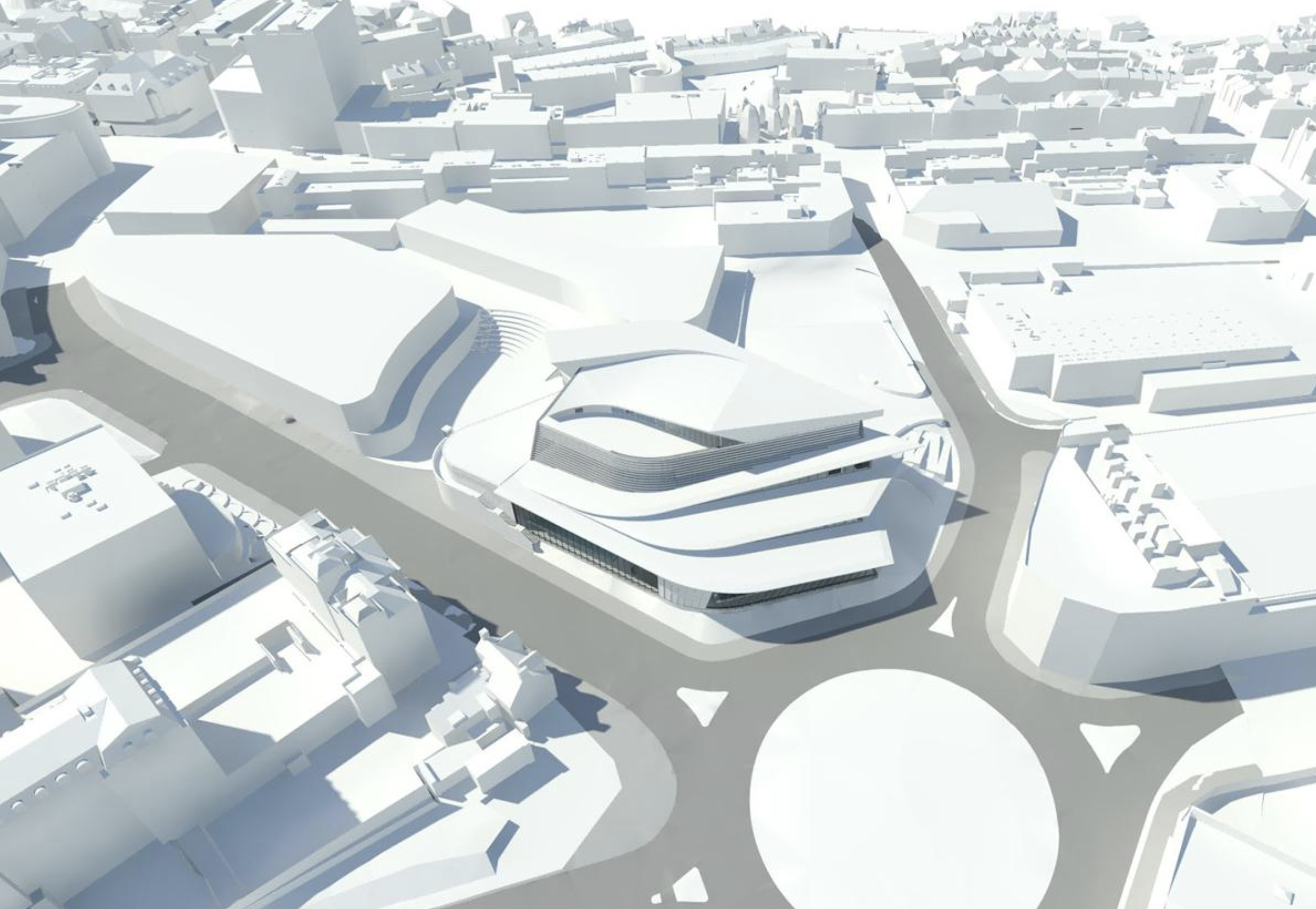

But Exeter has plenty of plans for more. The UK’s first Passivhaus leisure centre is being built in the city centre, a 53-unit care home is under construction and 13 homes are reaching completion, plus there are 30 homes with planning consent and a pipeline of around 500 more with planning applications due to go in. Osmundsen explains that one of the main reasons for investing in Passivhaus was to tackle fuel poverty. But there is still an issue over awareness.

“People don’t understand what a high-performing home is. Nobody really understands that the homes they’re living in are unhealthy and are having a detrimental impact on their health.”

This lack of understanding is illustrated by the misconception that residents of Passivhaus homes are not allowed to open their windows. Nevertheless, Passivhaus homeowners with feline friends may want to think twice. A pamphlet on Passivhaus published by Norwich City Council warned that cat flaps are banned, unless you have a “Passivhaus-certified one, which can be costly”.

Finding a contractor or consultant to work on a Passivhaus project can also be difficult. Bere has seen an improvement of late, but it wasn’t always this way. “For over 10 years I’ve spent far more time on site that I should have done with contractors trying to make sure they knew exactly what they should be doing and trying to check that the operatives were doing what they were supposed to be doing and not taking shortcuts behind my back. This is all very costly for us as a practice and is not very encouraging to other architects.”

In Exeter, the cost and paucity of contractors has also been a problem. “When we first started developing 10 years ago, there was a significant cost premium for Passivhaus,” says Osmundsen. “It’s only since they lifted the borrowing headroom [on councils] that we’ve been able to upscale Passivhaus.”

“A lot of contractors have already got a busy pipeline so they are not necessarily attracted to doing more perceived challenging projects,” says Osmundsen. “Engaging with the contractor marketplace has been challenging.”

Four years ago, Brussels introduced a law that all new buildings must be built to Passivhaus standards. Oslo did the same in 2014

She also bemoans the lack of training. “The professional institutions aren’t really training or preparing their consultants in terms of building to these newer, more high-performing levels.”

Bashar Al Shawa, a Passivhaus designer who is studying for a PhD at the Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering at the University of Bath, is also aware of a reluctance by building firms to get involved. “Contractors often complain there are delays associated with Passivhaus,” he says. “Every step of the project they have to check that everything is in place as you don’t want to have the house ready and then discover a major issue and have to knock out walls.”

The Passivhaus Trust is trying to tackle this reluctance among construction firms. The group is offering advice to contractors about how to bid for projects that need to meet the standard. “We see some contractors who are scared of Passivhaus and price it in as a risk, which means you get a high tender,” says Palmer. “Or, we see contractors who ignore it [the risk] and price it as a normal job. Then halfway through construction they are struggling to deliver.”

Another factor that is seen as a problem is installing mechanical ventilation heat recovery systems (MVHR), which are vital for Passivhaus. Again, however, backers of the standard are not perturbed by this. Palmer admits MVHR has had a “bad press”, but he adds: “That shouldn’t be a reason not to adopt it. You could have a badly designed, badly installed and badly maintained gas boiler, but nobody is saying you shouldn’t put boilers in. MVHR is great technology.”

Clearly there are plenty of things holding Passivhaus back. But, according to Bere, there is demand for it – at least in his experience. “I’m drowning in inquiries for very small projects from good people that we cannot assist, he says. “The problem is we need to find some way of making the very small projects affordable to do. I am often torn between what I want to do and what I know we can manage.”

The government’s climate change targets will not be met without the “near-complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions from UK buildings”

He gives the example of a woman in a small terrace in London, who is trying to keep her 90-year-old mother warm. “She has enough money to do some very basic work, but not enough to pay for the time we need to spend on the project,” he says.

So what are the prospects of things changing? Encouragingly, there are examples around the world where Passivhaus, or something similar, is being adopted or legislators are acting to make buildings greener. Four years ago, Brussels introduced a law that all new buildings must be built to Passivhaus standards. Oslo did the same in 2014.

Elsewhere, moves are afoot to tighten up the green credentials of buildings. In April, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio introduced legislation that will force the city’s buildings to cut their carbon emissions, or face penalties. It includes an eye-catching move to ban the construction of glass and steel skyscrapers. “It’s Passivhaus by stealth,” says Palmer. This builds on New York’s Greener, Greater Buildings Plan which requires buildings owners to register their electricity and water consumption.

In Vancouver, Canada, the authorities are actively promoting Passivhaus as part of its bid to be the greenest city in the world.

So what are the chances of seeing radical action in the UK? The government has vowed for net carbon emissions by 2050. But other indicators have been less positive. The Zero Carbon Homes plan was scrapped in 2015. It came along with the death of the government’s much-vaunted Green Deal as then-prime minister David Cameron was reported to have told aides to “get rid of all the green crap”.

Pressure is on the government to reinstate the Zero Carbon Homes plan. In a debate this month, Liberal Democrat peer Baroness Walmsley said: “The industry says it can do it, the planet needs it, so let us get on with it.”

The UK’s Committee on Climate Change, which is an independent statutory body, is also urging government action. A report published in February warned that the government’s climate change targets will not be met without the “near-complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions from UK buildings”. And that was before the target was changed to cutting emissions to near zero by 2050.

Palmer says what the climate change committee is recommending is “pretty close to Passivhaus”. He is keen too that people should not get too caught up with the term Passivhaus. “Passivhaus doesn’t have to be called Passivhaus. There’s a clear set of criteria and if you achieve those effectively you are there.”

All eyes are on the government’s proposed Future Homes Standard, which will set minimum environmental standards for all new housing

All eyes too are on the government’s proposed Future Homes Standard, which will set minimum environmental standards for all new housing. “Hopefully it will look quite similar to Passivhaus,” says Palmer.

He thinks the increased focus on climate change could spark action, too. “We have a different ball game with the climate emergency,” he says. “Paying more for a better product seems like a reasonable thing to do.”

Al Shawa is not convinced, however. “With this government, I’m not so sure,” he says. “They are not doing things that seem like common sense, like putting Passivhaus in law. I’m not very optimistic.”

Bere is also pessimistic. “The Conservative government is clueless and doesn’t seem to care,” he says. While Boris Johnson at least mentioned tackling climate change in his inaugural speech, there is no evidence yet of a huge shift in policy.

Bere adds: “My only hope is that the youngsters, Extinction Rebellion and Greta [Thunberg] will just take over. Patience is running out.”

He hopes that people will eventually see there is no alternative. “I think people are going to understand that the only way to properly address the [climate] emergency that we face is by doing nothing less than Passivhaus.”

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238